Postrevolutionary Modes0

An Essay about Transgender Women and Fashion

by Leah Tigers

Dedicated to the memory of Theodosia Markarian (1983-2023).

…to the lady and her acquaintances there was something heroic in living as though one were much richer than one’s bankbook denoted.

~ Edith Wharton, House of Mirth (1905)

0. Prelude (The Birth of Haute Couture)

According to the memoirs of one Amélie Carette, royal attendant at the last ever court of France, the empress had a favorite pair of earrings. They were “magnificent earrings, forming massive bulbs of diamond, which originally belonged to Queen Marie-Antoinette.”1 Such luxuries had been salvaged, presumably, before the infamous guillotine of the revolutionaries had liberated Marie’s head from her neck.

In her dress, comportment, and behavior, Empress Eugénie reinvoked that antediluvian dread. It was not just earrings; she preserved Marie’s prayer book, sat at her writing desk, collected her lacy veils. In February of 1866 she arrived to a costume party dressed up as Marie-Antoinette, pretending to be Marie-Antoinette. “I am thinking,” she wrote her sister during first pregnancy in 1853, “with terror… of Marie-Antoinette.”2

The cult of Antoinettism had acquired many true believers among noblewomen in the Second Empire. They wore the “fichu Marie-Antoinette,” the “pelisse Marie-Antoinette,” a hairstyle of mounted curls known simply as “the Marie-Antoinette”;3 their entire female custom was in no small part an exaggerated revival of Marie’s own century-old wardrobe. These women were the last princesses of a waning aristocracy, and at their most intimate, they knew it.

Most of their nights, however, were not spent at their most intimate, but at parties, galas, and grand balls declaring their undying splendor to the world. Appropriate compliment at these daily festivities was offered, ironically, through a rhetoric of authenticity: to have “great simplicity,” an “absolute want of pose,” and be “totally devoid of affectation” – as Eugénie and her husband Louis Napoleon were so endlessly flattered in memoirs by the Princess von Metternich4 – was the absolute zenith of nobility. Under this amnesia of tactful praise, it was almost possible to forget what the revolution had destroyed.

Just consider what a pureblooded royal had to endure to find a serviceable dress for “Mondays” at the Napoleons. Before all else, she had to endure the Napoleons. Louis was not “of the blood,” not a Bourbon, not an Orléan; not, even, of an original genius like his uncle Bonaparte. When in 1853 he first petitioned for a wife amid legacy royalty of the English, Queen Victoria spit venom in protest:

“You know what he is, what his moral character is… what his entourage is, how thoroughly immoral France and French society are – hardly looking at what is wrong as more than fashionable and natural – you know how very insecure his position is…”5

Declared unmarriageable by old crowns, rejecting tradition despite himself, Lou elevated to bride a mere countess, the Spaniard Eugénie de Montijo, whom he previously pursued only as a mistress. Though she was no Marie-Antoinette, little wonder why she strove to be one.

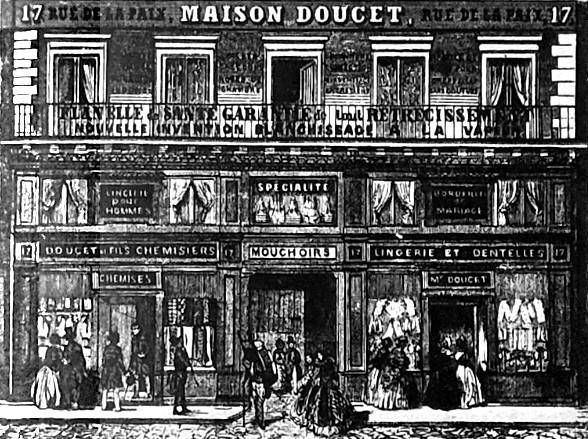

Should the raw fact of empire loosen these traditional prejudices, as it did for most of continental Europe, a pureblooded royal then had to endure a shopping trip. Rapidly fading were the days of couture à façon, when fine dressmakers worked at court, or at least, narrowly obeying dictates from nobility. Instead, this Napoleon (the third) had been obliged to fund “the Bourse,”6 mass renovations to popular shopping districts around the 2nd arrondissement, specifically to placate revolutionary discontent.7 In his words, the Second Empire must “encourage institutions intended for development of commerce,” to “satisfy legitimate interests,” thereby subduing the “vast demagogic conspiracy.”8

One brief carriage out to the Bourse revealed just whose revolutionary interests had been legitimated. Their names were literally emblazoned on the storefronts: House of Doucet, House of Laferrière, House of Aurelly, Pingat, or Worth. They advertised “objects of fantasy,” sold “haute novelties,” formed trade associations “de la couture”; in simplest terms, they were newly empowered business owners, perched well above the renovated clothing industry, inventing haute couture in all but name. Though they sounded noble and aristocratic, they simply made a lot of money, at a time when confusion between these two concepts had grown tremendously fraught.

And so our pureblooded royal had to put up with these goons too. Oh, she loved them, superficially enough; noble literature of the period is strewn with references to “the great Worth of Paris,” “the famous Worth,” proclamations that “No one will ever replace Worth’s for me”9 – to say nothing of the constant, florid descriptions of her conspicuous10 ball gowns, purchased always in the Bourse. The oldest, priciest, and most English house of haute couture was that of Charles Frederick Worth, who had emigrated from London, so to mention him repeatedly was a great brag.

Underneath these surface affections, however, was a roiling ambivalence. Monsieur Worth was again the premier example. Princess von Metternich, his lifelong patron, recalled needing “to overlook certain absurd little airs which he [Worth] gave himself, to say nothing of the rather overbearing attitude…”11 When in 1860 Charles fulfilled his first commission for Eugénie, the empress dismissed his use of rough silk as “curtain material”; so the ambitious tailor simply went over her head, reminding her husband such dresses must be worn to pacify the agitated silk weavers in Lyons.12 This then was what it meant for an imperial family to “satisfy legitimate interests”; Empress Eugénie wore the dress, sorely referring to it as her “political toilette.”

To the royal, such ambivalence was a perplexing disturbance. Few noblewomen could deny how fiercely this new industry of haute couture was dedicated to the cultivation of nobility. All her beloved Marie-Antoinette costumes, her Antoinettist trends, came down from these houses. Jacques, of the House of Doucet, would found France’s Historical Costume Society, and own the largest private collection of prerevolutionary gowns in the nation, on which his own designs were derived. Surviving fabric swatches from Charles directly reference royal portraits in the museums of London, antiquated, idealized representations of power before which, as a boy, he was said to have lavished “every moment.”13 There could be no doubt haute couture was passéiste, full of nostalgia.

The postrevolutionary dilemma was that cultivation of nobility was no longer restricted to nobles; that, moreover, French society was no longer even sure what “nobles” were. It included, perhaps, too much of the dressmakers themselves. Charles by no accident paired a bust of Napoleon with his own at his private château in Suresnes.14 More than one journalist delighted at revealing the hidden novelty of this “Napoleon of fashion,”15 “the only absolute monarch left in Europe,”16 who seemed to need royal patronage less than it needed him. “...[S]he called on the illustrious Worms, dressmaker of genius,” wrote Émile Zola in 1872, a clear riff on Worth, “before whom queens of the Second Empire fell to their knees.”17 From the earliest volumes of Harper’s Bazaar, 1867:

“...the Duchesses and Princesses approached and began talking to him [Worth] in a coaxing, pleading way, which struck me as being in strange contrast to the imperious manner in which women of their rank are wont to address tradespeople… these noblewomen gazed at him in speechless admiration…”18

Or Margaret Oliphant, who offered in 1878 the rare plural first-person: “...we obey him like slaves.”19

So our pureblooded royal who entered the House of Worth to affirm her royalty was forced, however subconsciously, to confront its precarity. Her serviceable dress ran upwards of, adjusting to inflation, fifty thousand dollars;20 the beauty of this purchase, could she even afford it, too often hid an ugly new debt. Her serviceboy Charles was a bourgeois, in the most timely, Marxian sense of that word, yet he likely outcompeted her financially. Profits ran upwards of six million a year.21

Humiliation by the surrounding crowd at a Worth salon was at once subtle and omnipresent. Nobility itself had been diluted. “Dollar princesses” littered the room: Drexels, Jeromes, and Vanderbilts from America22 (that mystical land without queens) whose business-brained, billionaire daddies had dowried them into loveless marriages with bankrupt English lords. Not even England was safe! Trading money for royal titles, vacationing in France, their presence at salons was derided as “an alien horde,” “gilded prostitution,” “poison in the veins.”23 More redblooded patriots like the J.P. Morgan family had dispensed with this royal charade altogether, yet still shopped freely at Worth. It was these families Charles intended when he once remarked, “I like to dress them, for, as I say occasionally, ‘they have faith, figures, and francs’ – faith to believe in me, figures that I can put into shape, and francs to pay the bills. Yes, I like to dress Americans.”24

Far worse than les Américaines were the demimondaines; that is, to less polite society, the whores. These were mistresses, actresses, and related upstarts of ignoble birth whose rich lovers and/or employers sugared them with a Worth dress. Disregarding propriety, Charles was only too happy to serve. Outfitted beside noblewomen titled “de” or “von” or “the Third” were Sarah Bernhardt, Lillie Langtry, Cora Pearl: these were street names, stage names, yet they fancied themselves royalty. A rare few were eventually wifed, and truly became it.

“It was a day,” recalled Charles Worth’s own son, Jean-Philippe, “when fashionable and fast women were veritable queens.”25 This was only sometimes hyperbole. Queens were on the decline, but “queenliness” was ascendant. The earliest “beauty queens” of the earliest beauty pageants were officially sanctioned in these decades;26 journalists trafficked freely in the word. “She is truly the queen, the fairy that commands and transforms,” one reporter wrote of Miss Bernhardt on stage.27 Lillie Langtry, who performed in theaters as Marie-Antoinette, recalled in her memoirs,

“I became more and more reckless, allowing insidious saleswomen to line negligees with ermine or border gowns without inquiring the cost… For the first time in my life, I became intoxicated with the idea of arraying myself as gorgeously as the Queen of Sheba…”28

The rarest, most grotesque injury to royal blood was this beautification of a working woman. Worth’s was the first major couture house to employ living mannequins at their salons, who formed a “curious spectacle,” “dressed up in clothing, jewels, and laces fit for the gala wear of so many empresses.”29 Onlookers were hard-pressed to tell the difference between princess and pauper.

The most glamorous of these mannequins, however, was never disputed. She was a French woman by the name of Marie-Augustine, who had been Charles’s first ever model. They met as young, unknown quantities, both underpaid, working retail at a lesser house. Described in those years as a “timid, modest woman who blushed when she spoke,”30 she had almost no dowry to her name. Their marriage arose as an insecure, middle-class affair. Fifteen years later, on the floor of her House of Worth, she alone wore a diamond tiara.31

1. Transvestites (Dandy Theory)

“There is as yet in England no state of social decomposition [as in France],” boasted English fashion magazine The Woman’s World in 1887.32 This line occurred in its regular column on Paris, where praise for Maisons Worth, Doucet, et Cie was practically a daily prayer. Comedic irony was not intended by its writer. The Second Empire had fallen, but haute couture remained. Mighty Albion, destroyer of Napoleons, could rule the world in everything except fashion, where “what Paris thought and what Paris were, formulated itself into an iron law.”33

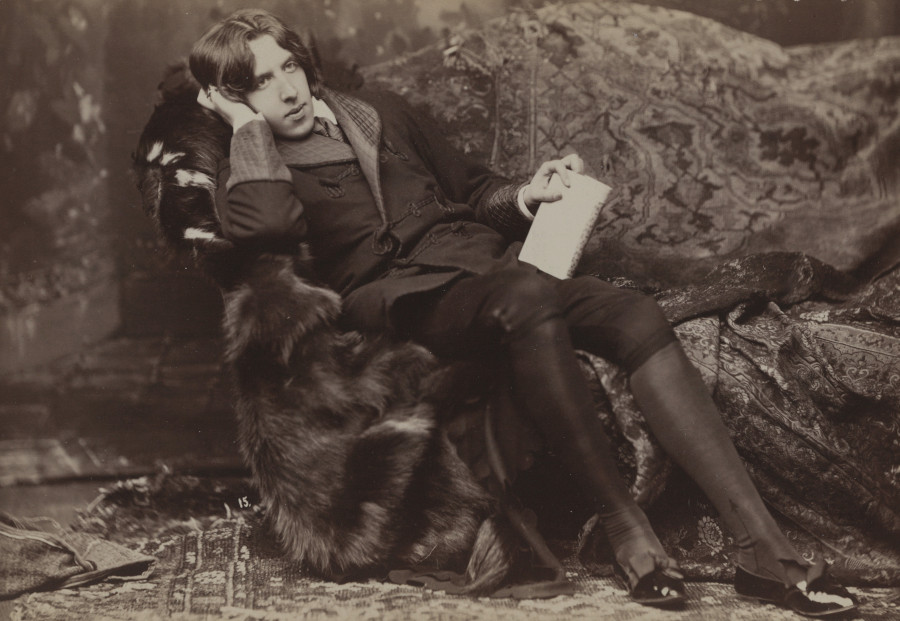

One who did intend comedic irony was the editor for Woman’s World, a dapper wit in his early thirties by the name of Oscar Wilde. Under his advisory, English fashion discourse had been elevated, interrogating such notions of national identity, class, even suffragette appeals for dress reform. Several articles praised crossdressing, particularly “women wearers of men’s clothes,”34 while Oscar, then growing out his hair, asserted “dress of the two sexes will be assimilated”35 by the twentieth century. Evidently, distinctions of class were not all that was decomposing.

While this decomposition never achieved completion, it did achieve high fashion. Oscar was invested, but dissatisfied; lecturing as a self-declared “professor of aesthetics,” he advocated reform far more democratic than the capitalists. “A dress should not be a steam whistle,” he declared, “for all that M. Worth might say”; “At present we have lost all nobility of dress.”36 Rather, truly noble spirits were to favor the tea gown, an informal, androgynous, unstructured silhouette. These critiques grew so abundant they, in turn, changed what dresses M. Worth produced.

Making real use of his fake professorship, Oscar toured often in Paris, sometimes in America. An Irish-blooded anarchist, disgusted by the idea beauty should be withheld by birth, he fell in quickly with bottomfeeders of the haute couture set. To actress Sarah Bernhardt, he sent frequent letters, offered a feature in Woman’s World, and composed lead role in his play Salome. To his friend Lillie Langtry he gifted a photo session with famed New York photographer Sarony,37 who snapped her in Worth’s Sunday best. Oscar enjoyed his own photographs with Sarony, where he struck an unexpected pose, reclining idly with a long jacket in the posture of a female nude.

Odd men like Oscar were not unknown to Europe; in the century since the French Revolution, they had become a certified literary type. Like Julien Sorel, the unlikely hero of Stendhal’s The Red and the Black (1830), he had an “almost feminine delicacy,” and might even be taken “first for a girl in disguise”;38 like Henry Pelham of Bulwer-Lytton’s Pelham (1828) he averred “none but those whose courage is unquestionable, can venture to be effeminate.”39 Like the cryptic “I” in the poems of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil (1857), he might dare hermaphroditic dreams of “a boy’s torso joined to Antiope’s hips”;40 or, like fevered scion Jean Des Esseintes of Huysmans’s Against Nature (1884), he could even have “got to the point of imagining that he himself was turning female,” thus experiencing “an artificial change in sex.”41 When, in 1895, Oscar was convicted of gross indecency, in a tendentious trial citing his published allusions to Against Nature as evidence of sodomy, his life truly became this art.42

The fop, flâneur, idler, beau, lion, aesthete, chevalier, or, under his commonest title, le dandy, was this odd man of fashion. Needless to say, there was something transsexual in him, but there was more than this. The school of literary dandyism was self-aware, housing an entire annex of theorists, cultivating a vast mythology about everything more they were.

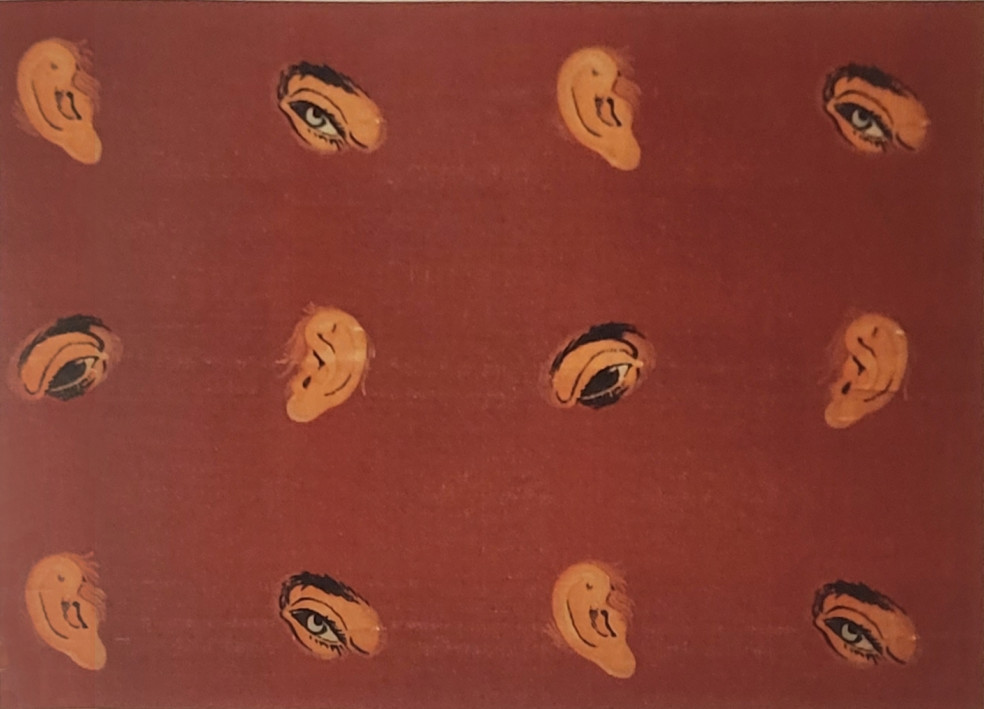

In dandy theory, any transgender aspect was caught up in the modern paradox of democratized nobility. Thus, “Dandyism appears especially in those periods of transition when democracy has not yet become all-powerful, and when aristocracy is only partially weakened and discredited” (Baudelaire, 1863).43 Being “led by the demon of contradiction” (Gourmont, 1896),44 dandies reappreciated a stock vocabulary of aristocratic decline: decadent, oriental, plastic, sick; the word “dandy” itself, initially an insult; and of course, androgynous, effeminate, feminine, female. These men were, in the inchoate slang of their times, queening.45

Other instances of his paradox engaged him in mutual fascination. Almost every literary dandy or dandy-adjacent, from Marcel Proust to Charles Dickens to Stéphane Mallarmé to Oscar Wilde, knew haute couture, wrote on it, and mentioned its designers by name. (Stéphane, like Oscar, ran a lady’s fashion magazine, even pretending to be a female journalist.)46 Scrupulous dress was central to the dandy mythos. This was no surface interest in cloth, their theory defended, but rather “a certain manner of wearing clothes” which “plays with the regulations [of ‘established order and nature’]” (D’Aurevilly, 1845).47

Theorists claimed this dandy manner of clotheswearing, though refined by their own milieu, had occurred in ancient Rome and the Americas. They named direct inheritance from George Selwyn, a British statesman of last century who had “disguised in a female dress.”48 The theoretical turn had illuminated specks of dandyism on everything, and we can detect our own. It possessed couturier Charles Worth49 when he snapped to correct his patron, Princess von Metternich, “Tell them it is I who invented you.”50 It overtook general Napoleon, the first, when praising a lowborn marshall who delivered him numerous victories on the battlefield: “There you see true nobility of the blood.”51 It even contaminated women,52 yes, women, to everyone’s consternation: there was dandy aspiration in Empress Eugénie, leader of the Antoinettist cult; in Sarah Bernhardt, onstage in “mannish” haute couture tea gowns; in Marie-Augustine Worth, a bourgeois wife adorned by a crown.

This final point was a major source of contention in the new dandy metaphysics. Inside every dandy was a little Bonapartist, sometimes a big one, but Napoleon gave women none of the freedom revolution gave him. “During the Revolution,” he said, “women rose up in rebellion… men were obliged to check that idea. Disorder would reign entirely in society if women came out of the state of dependency where they ought to remain.”53

Such a flagrant double standard manifested in dandy theory as incoherence. Baudelaire, its worst offender,54 asserted “Woman is the opposite of the dandy” because “Woman is natural,” while at the same time valorizing “dandyism as a frigid female”55 – what his great critic Walter Benjamin clarified to mean “renunciation of the ‘natural’” in “the androgyne, the lesbian, or the barren woman.”56 If the dandy was opposed to woman, naturally, then inversely, the unnatural woman was prophesied as the dandy’s ultimate form.

In a rare but instructive instance where these public changes to sex preempted the class revolution, her ultimate form had already been realized, almost perfectly, in one woman, as early as 1770. Like the dandies, there is a mythos around the Chevalière d’Eon, which even overlaps. “Men of fashion” were recorded loitering around England’s exclusive gaming houses, discussing d’Eon, “comparing notes,” and generally highrolling through life, gambling thousands of pounds on her “true sex.”57 A more respectful dandy was that wit, George Selwyn, praised by the later movement. In a letter of late 1777, he wrote, “Mademoiselle d’Eon goes to France in a few days; she is now in her habit de femme, in black silk and diamonds… I shall have sight of her before she goes.”58 If members of the d’Eon Association, a small Berlinese transvestite club of 1930, or Chevalier Publications, a private trans zine producer of the 1960s, did not recall the obscure Selwyn, they at least recalled their beloved Chevalière.

Like the dandy, Charlotte d’Eon had risen up her station in life. Reared (as a boy) in a provincial noble family of low rank, she was by the time of her transition a prestigious diplomat, veteran, and scholar, with sufficient power to repudiate the French king. Like the dandy, her repudiations were filled with enlightened individualism. “You know I am crazy about liberty,” she wrote; or again, “I will always go my own way”; or again, “a woman in every country has the freedom to dress as she pleases.”59 Like the dandy, she lived well above her means, generating much conflict with the royal family. On mission to England she bought, with taxpayer money, at least four thousand bottles of wine; for years she purchased over a book a day, often rare manuscripts; and, despite living alone, she employed a household of more than fifteen servants. Like the dandy, she did this all in considerable debt, at just the moment the French economy collapsed; and when the Revolution clipped at its heels, like the dandy, she offered revolution her moderate support.

All that was absent these dandy accents on the portrait of a trans woman was fashion, but this entangled her transition. “I am terribly mortified at being what nature has made me,”60 Charlotte had written; so, be something else.

Since serving in the Seven Years’ War, Charlotte exclusively wore her military uniform, with her medal of honor, the Cross of Saint-Louis. The uniform maximized her prestige, so even after she declared herself a woman, she would not remove it. “I would prefer to keep my male clothes,” she wrote, as any female dandy would, “because they open all the doors of fortune, glory, and courage. Dresses close all those doors to me.”61

What soothed her entrance into skirts was a promise of greater nobility. Now the speculation of every tabloid, she was invited to meet, for the first time, that queen to end all queens, Marie-Antoinette. “I shall handle her trousseau,”62 Marie mediated. The queen’s dressmakers were scandals in their own right; she collaborated with unmarried businesswomen of common birth, a new class of so-called “fashion merchants” who provided an early blueprint for haute couture. “I am pleased to wear it,” Charlotte would accept, “because it admits me to the Regiment of the Queen.”63 In Charlotte’s unpublished memoir, dialogue with Marie’s fashion merchant64 consumes half the narrative. “You will now have to dress me in the Queen’s gowns,” Charlotte declared, “which you brought along in keeping with the decorum appropriate to my age and my status.” For all of her days she would gloat, “the very woman who dresses the Queen did not turn up her nose at dressing Mademoiselle d’Eon grandly.”65

Moments of queenery like this were the climax of the dandy monomyth, but never the conclusion. The conclusion was, always, downfall. In every instance, this was at least debt;66 thus went Charlotte, who died in poverty in 1810, upon which a team of dismayed coroners redeclared her a man.67 In famed instances, there was more: a sodomy charge, a prison sentence, fleeing the country;68 perhaps all three, as with Oscar Wilde. Near the end of his life, he retrospected, “I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion… I ended in horrible disgrace.”69 These new laws of bourgeois liberalism invited their own violation, but were unsparing in their punishment. The best one might hope for was quarantine on some remote hamlet, like a Napoleon, or Jean des Esseintes from Against Nature, to maintain aristocratic fantasies in harmless isolation.

But the excesses of fashion, this dandy manner of clotheswearing, still haunt our liberal culture. In 1910, when a relatively young doctor named Magnus Hirschfeld – a touch of a dandy himself – termed what was also called “Eonism” as “transvestism,” he was adamant the word was not about mere vestments. Rather, he wrote, “Clothing speaks: I am a prince or a beggar.” That which revolution exposed as superficial and changeable must for that very reason be enshrined as an “expression of mental conditions,” the “unconscious language of the spirit.”70 Obviously this was a paradox, the precise origins of which it has been, thus far, the purpose of this little essay to uncover.

2. Transsexuals

“And of course I was French,” reckoned photographer Chantal Regnault, on why subjects in her pictures were fond of her, “and there was this whole mythology of France and glamour.”71 Her subjects were American, typically Black, typically queer, dancers, models, queens of the underground ballroom circuit in 1980s New York and Jersey. Their eldest participant-historians tended to agree. “The history of balls?” remarked Marcel Christian LaBeija, having organized them so far back as ‘62, “Marie-Antoinette would have balls, and toss diamonds to the winners.”72 Icon Kevin Ultra Omni, who walked his first ball in 1980, offered an oral history over four decades later:

“Let’s take the year 1776. Let’s go back to Paris France when Queen Marie-Antoinette and King Henry the… I think it was, I’m not sure, the thirteenth or one of those numbers. They gave balls, and they were costume balls…”73

In the vocabulary of ballroom, there is even a pseudo-Gallicism: queens who scored poorly with judges were chopped, a knowing reference to the revolutionary guillotine.74

No deep insight is required to suggest these proclaimed origins of ballroom have an air of invented tradition. Their own proclaimers did, tongue firmly in cheek. Dorian Corey, ballroom pioneer and costume designer, added a frank twist to the drag staple of Marie-Antoinette, portraying her mid-decapitation.75 In 1986, detailing the legendary Paris Dupree – a queen never chose a name more redolent in Francophilia – Marcel Christian wrote, “Many years ago there was a famous whorehouse in Paris known as The House of Dupree… Could there be some relationship? No. Of course not!”76

A less fantastic origin, no less acknowledged, split off from the Harlem Renaissance. Unsettling the hegemony of money, wit, and beauty as exclusively white attainments, the “New Negro” of 1920s Harlem simply was the Black dandy;77 modern, individualist, and tentatively bisexual, the exemplary Langston Hughes attended “ball[s] where men dress as women and women as men,” describing them as “spectacles in color.”78 There were, participants grieved, “no Negro judges,”79 so ballroom evolved to unsettle this hegemony too. Yet already in this primordial phase, as described in Strange Brother (1931), a sympathetic novel by white patron Blair Niles, there loomed “towering curled and powdered head-dresses of the Marie Antoinette period.”80 Various Harlem intellectuals would literally just emigrate to France, but not queens like these; not yet.

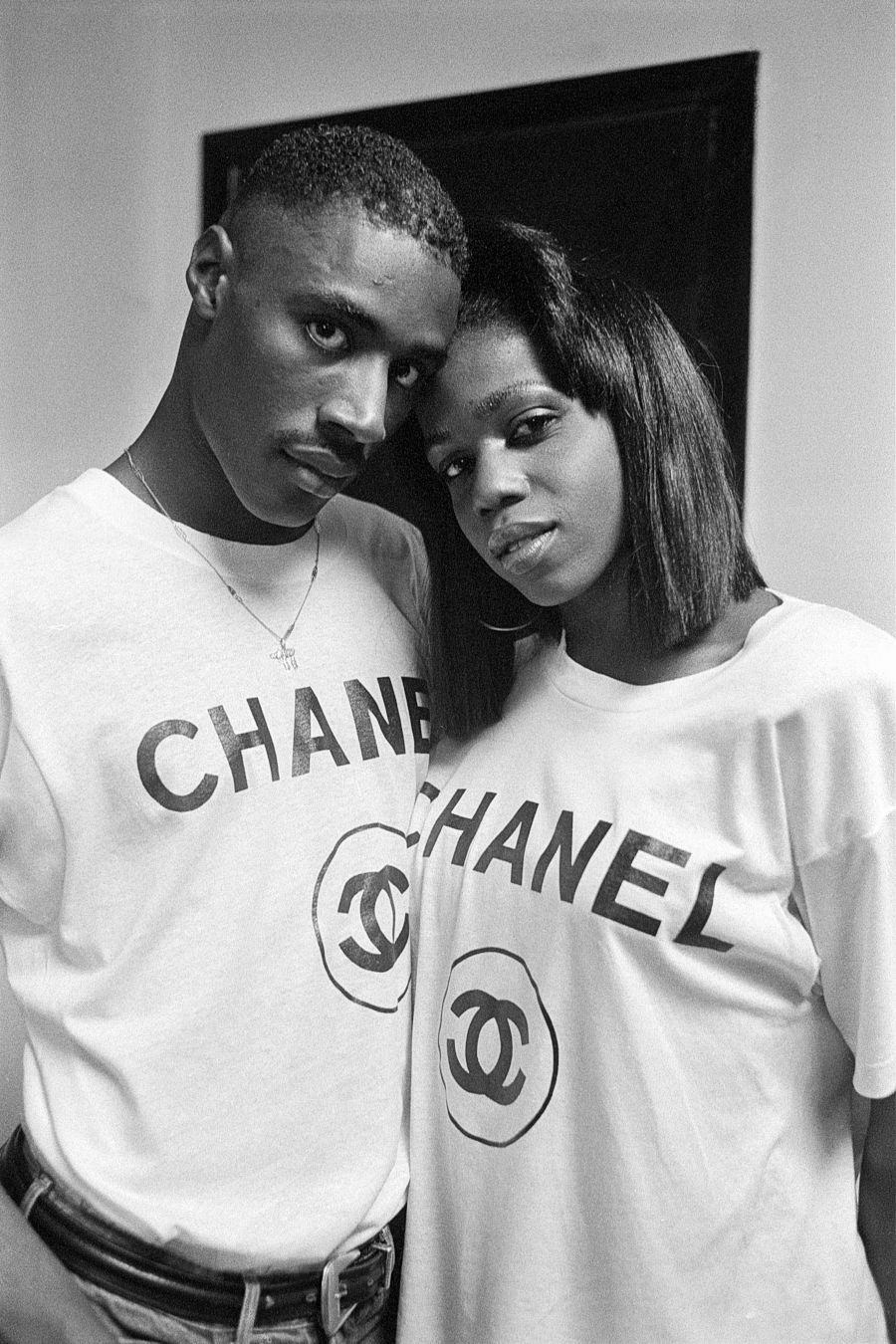

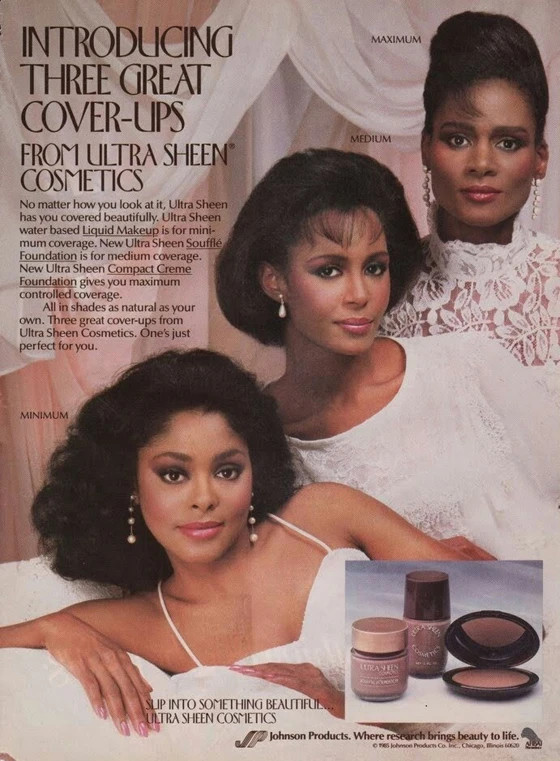

For the ballroom children, like their expatriate ancestors in the Harlem Renaissance, were soon to discover that France was a real place. Already their range of reference, never much bound by chronology, had grown frighteningly contemporary. A house system for group competition developed in the 1970s, styled not after royalty but the postwar maisons of haute couture. In younger generations this styling was explicit. Members from House of Dior (‘74), House of Chanel (‘80), and House of Saint-Laurent (‘82), all infringing copyright,81 competed alongside originals like LaBeija (‘68), Corey (‘72), or Dupree (‘75).82 Newer houses Ebony (‘78) and Africa (ca. ‘85) wove Black pride directly into their names. Younger femme queens in the scene more often identified explicitly as transsexual women; even more often, they aspired to model women’s fashion.

Of course such children were either wearing haute couture, or wanting to. “If you down with the House of Chanel, you dress with Chanel, you know, Chanel clothes.”83 Among queens of the ‘80s, that was a tall order. Driving the superfashionable House of Xtravaganza (‘82) to a ball out of state, their busman remembered a prior engagement:

“One time last year up in Boston the tour guide was telling them about some of these ladies’ stores with all this name designer clothing. She asked them if the kids had seen them before, and the kids were wearing them.”84

Yet this had not been with the Xtrava house, “renowned for its transvestites, impossible beauties,”85 but the daughters of millionaires.

To afford these designers, ballroom children worked honestly, saved carefully, and studied hard; they also stole, frequently enough that their dance technique, voguing, was speculated to have originated on Rikers Island.86 Sex work, particularly among femme queens, was not uncommon. “90% of them are hustlers,” estimated young Venus Xtravaganza, “I guess that’s how they make their money to go to the balls.”87 An admitted hustler herself, one leading memory between her birth family was that she “liked to dress in a lot of fancy designer clothes.”88 Among the more unusual stories, there was one (cis) woman, Shamecca, born Beverly Ash, who walked a House of LaBeija “Harlem Fantasy” ball in 1982. She wore a $3,500 gold lamé dress displayed in Saks Fifth Avenue that very morning, and her boyfriend headed a drug trafficking ring.89

Before the decade was out, both these women would be murdered, in circumstances directly tied up in how they got their money. These were enormous tragedies in the community, but the normal ones were dire enough Marcel Christian circulated a questionnaire at a Dupree ball in ‘86, asking, “Is Ball Fever worth it? …worth what? …the trip to Rikers Island when you got busted for stealing that leather suit… It must be, you’re here, aren’t you?”90

This updated demimonde, Blacker, queerer, and more American than any before it, was as yet almost willfully ignored by the French haute couture houses themselves. But they could not hold out much longer.

Literally, there were no more empresses of the French to dress; figuratively, prospects appeared almost as grim. Customers dwindled. The foundational House of Worth shuttered in 1956, after four generations, and they were not alone; over eighty houses, or four fifths of the haute couture registry, vanished without replacement across two decades after the war.91 When one of the last profitable couturiers, Christian Dior, died of an expected heart attack in 1957, his obituaries mourned the loss of “industry prosperity” itself.92 The surviving wave of models and designers, whether disaffected veterans or groovy young libertines, habitually conversed on their trade in a language of death: “Couture is for grannies” (Brigitte Bardot); “Let’s kill the couture” (Emanuel Ungaro); “Haute couture is mortally wounded” (Cristóbal Balenciaga); “Haute couture is dead” (Emmanuelle Khanh).93 In this murder plot, they anticipated the socialist revolts of May ‘68.

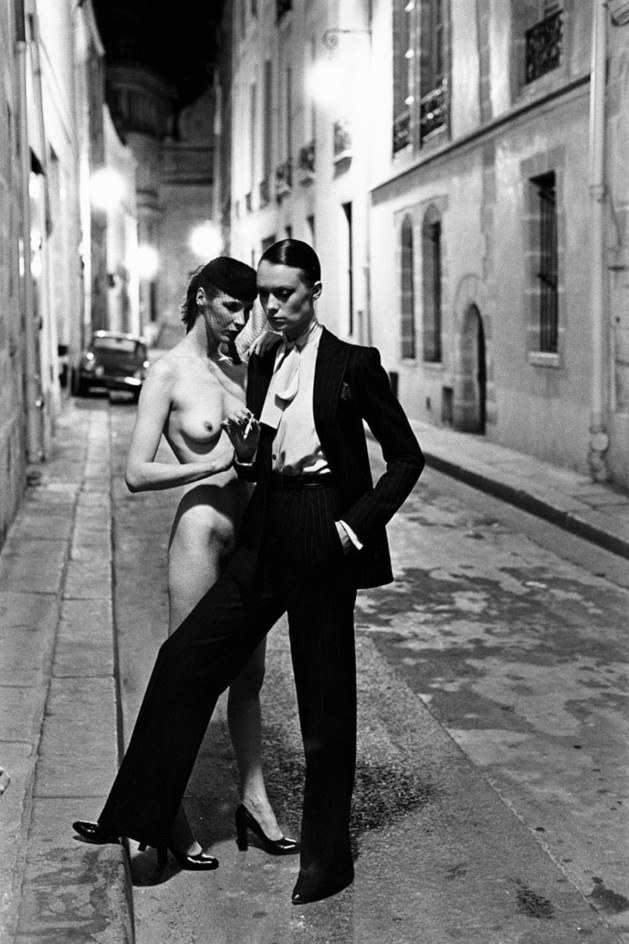

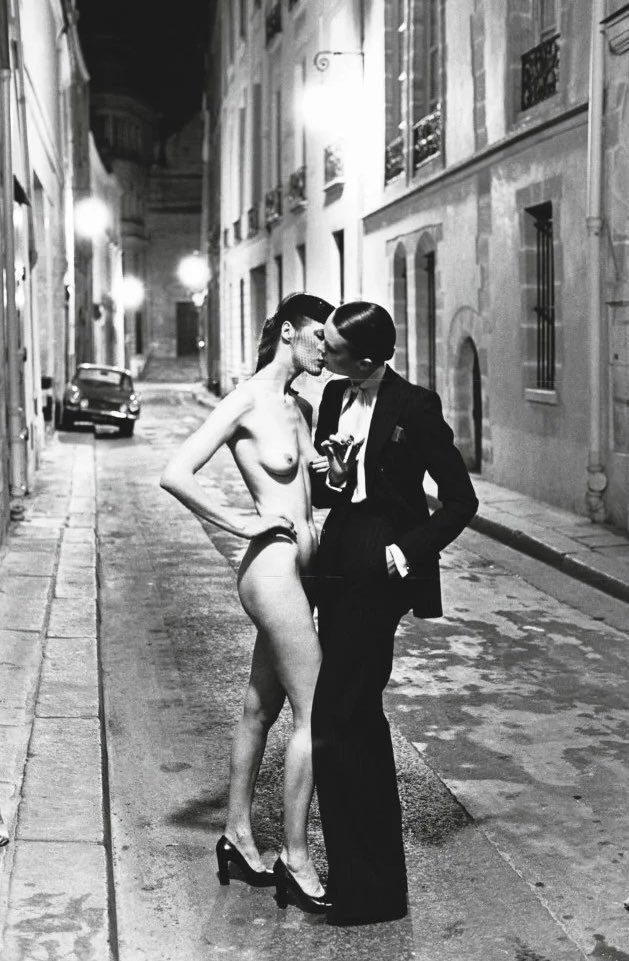

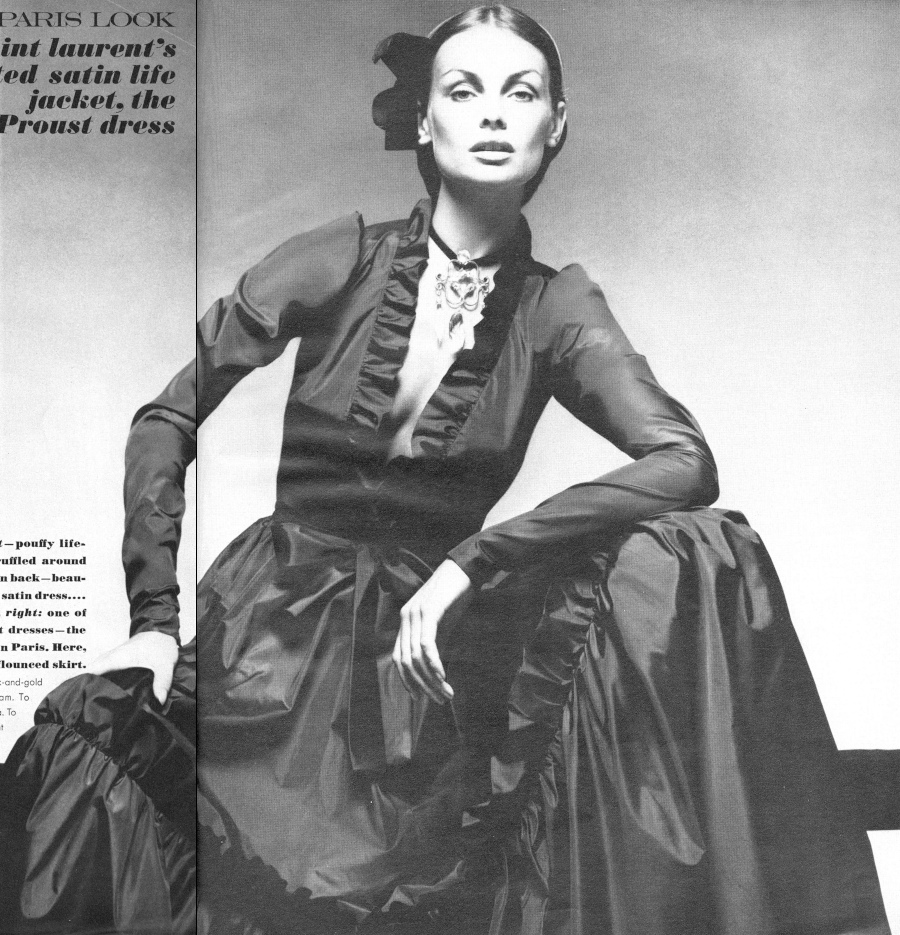

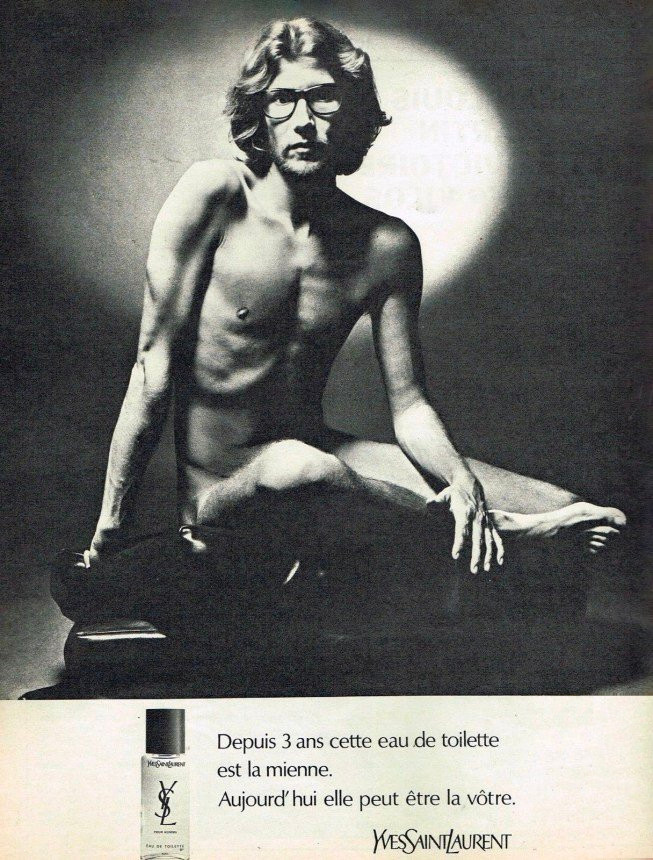

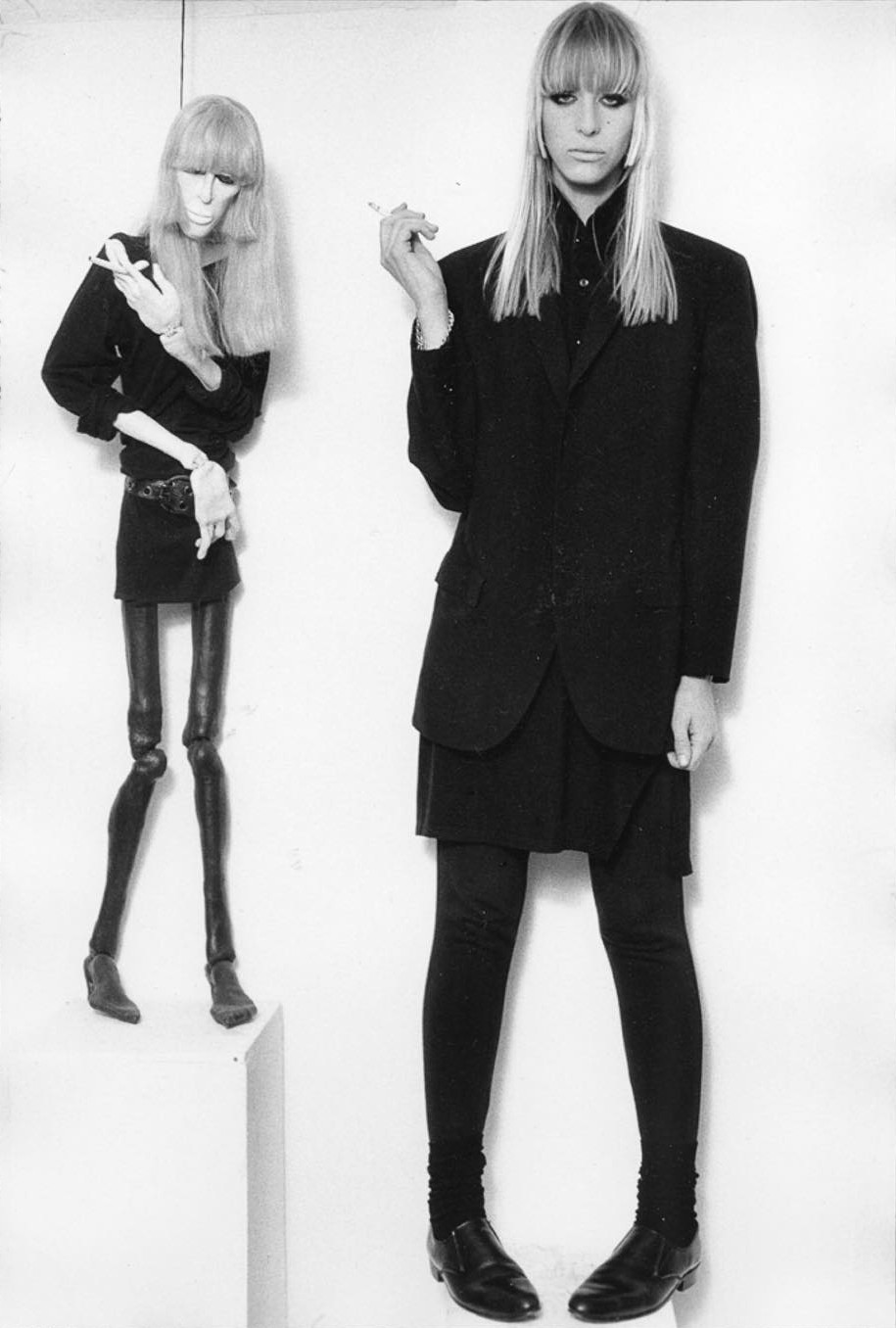

Not earliest, not eagerest, but surely the most visible participant in this plot was the young designer Yves Saint-Laurent, who inherited the Dior line for six seasons at the surreal age of twenty-one. Attracted to fashion in an era of renewed class struggle, Yves was of course a renewed dandy. He was gay, and waifish, even suggesting “Maybe I didn’t have what it took to be a boy.”94 He designed dresses out of descriptions from Marcel Proust and, following success of his own Saint-Laurent brand, named rooms in his vacation home after Proustian characters. He grew his hair long, like Oscar Wilde, and in a step much further, dressed his female models like Oscar Wilde too. Papers admonished with overawed descriptions of “Yves’s transvestites,” but such dandy interventions were, by definition, never exclusive to gender.

Yves Saint-Laurent Gallery

As part of his far step, Yves encouraged his transvestite haute couture to be consumed democratically,95 through mass produced ready-to-wear lookalikes. At his Rive Gauche storefronts, opened to the Americans in 1968, an anxiously middle-class, feminist-minded, careerist young dandette could purchase a Wildean pantsuit of her very own, without any fittings, for the merely absurd price of (adjusting to inflation) $1,100.96 Lower down the scale, a $300 middy blouse brushed her reality. It was this gradual redefinition of haute couture as upmarket ready-to-wear, a literal cheapening, which ballroom children stole, which even made haute couture stealable; and it saved the industry. But what a price to pay, in both respects.

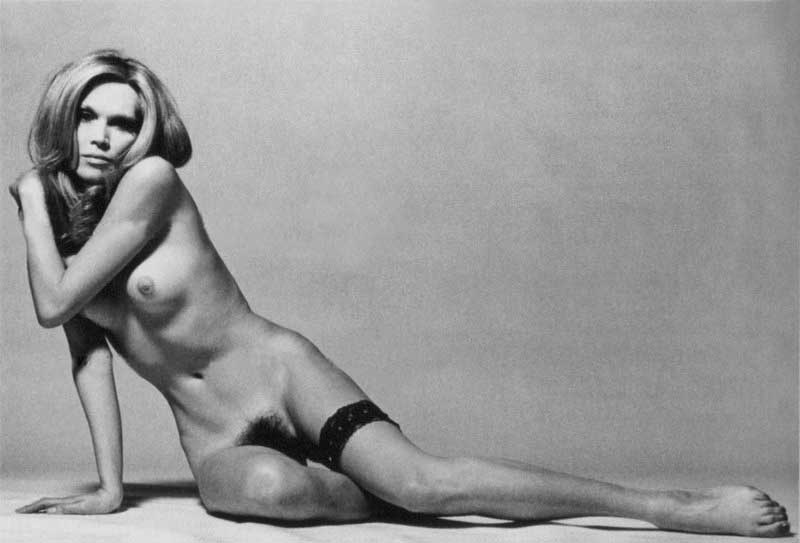

Among a slew of downstream effects, redefining haute couture exploded its modeling sector. Extreme profits from a new audience using secondary lines of production with rapid turnover generated aggressive demand to model just about everything. Eager to fill this vacuum of fashion workers were low women with a special genius for opportunity; and a few did in fact slip through. There was, for instance, the rising nobody April Ashley, whose testimony betrayed falling barriers to entry early as 1960:

“Miss Marshall [the agent] asked me to twirl. ‘You’re a natural,’ she said and took me on the spot. This was a surprise because modelling was then far more formal than it is now, training was considered essential, but again I had been dropping heavily the magic name… ‘Paris, yes, I’ve been working in Paris for the past four years, Miss Marshall, that’s why you don’t know me – Paris and Milan – appearing for Schiaparelli, that sort of thing…’”97

Properly, the couturière Elsa Schiaparelli (of noble birth) had only ever gone slumming to seedy cabaret around the Bourse, where she viewed April performing onstage. Opportune lies were, again, part of April’s genius.

Their success shocked even her when, after a year on the job, she overheard several of the altruistic old men who seek company with models addressed as “m’Lord”; when, three years later, the most compromised among them proposed a marriage. For the rest of her twenties April Ashley became the Right Honorable Lady April Corbett, future Baroness Rowallan, potential First Lady of Tasmania, etc., etc. After her twenties, though, her downfall: the husband obtained annulment at court on grounds that “the respondent [April]… was a person of the male sex.”98 British society, torn between its hatred of transsexuals and adoration for medieval social hierarchy, has never known quite what to make of her.

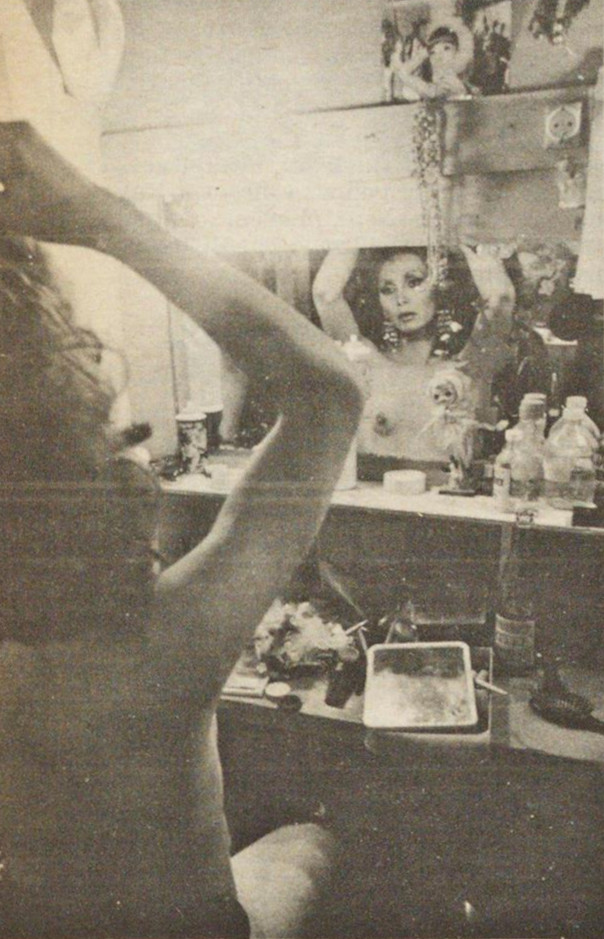

Nor was April alone in her embarrassment of success. There were coworkers in her Parisian drag shows. Bambi (lately Marie-Pierre Pruvot) performed while taking a degree to teach high school literature, citing admiration of Stendhal and Proust.99 “I love fashion,” she said, “I always have.”100 In late life, she was honored lead model for a Mathieu Matachaga 2014 collection themed on these early years.

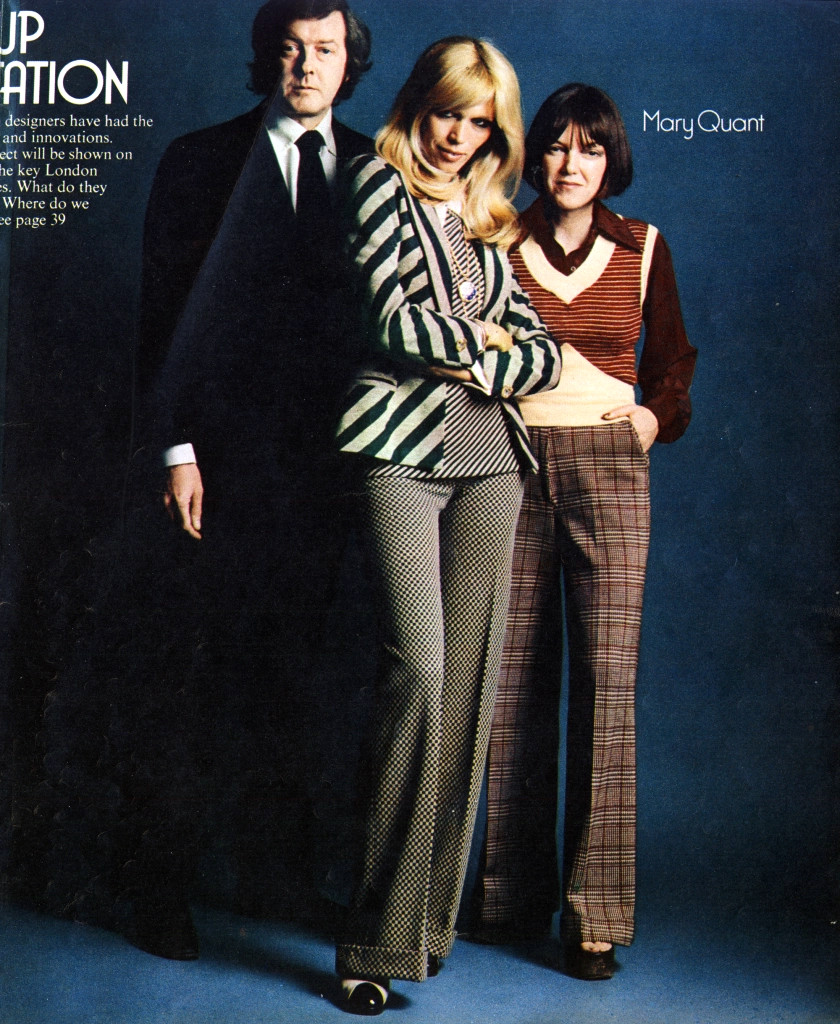

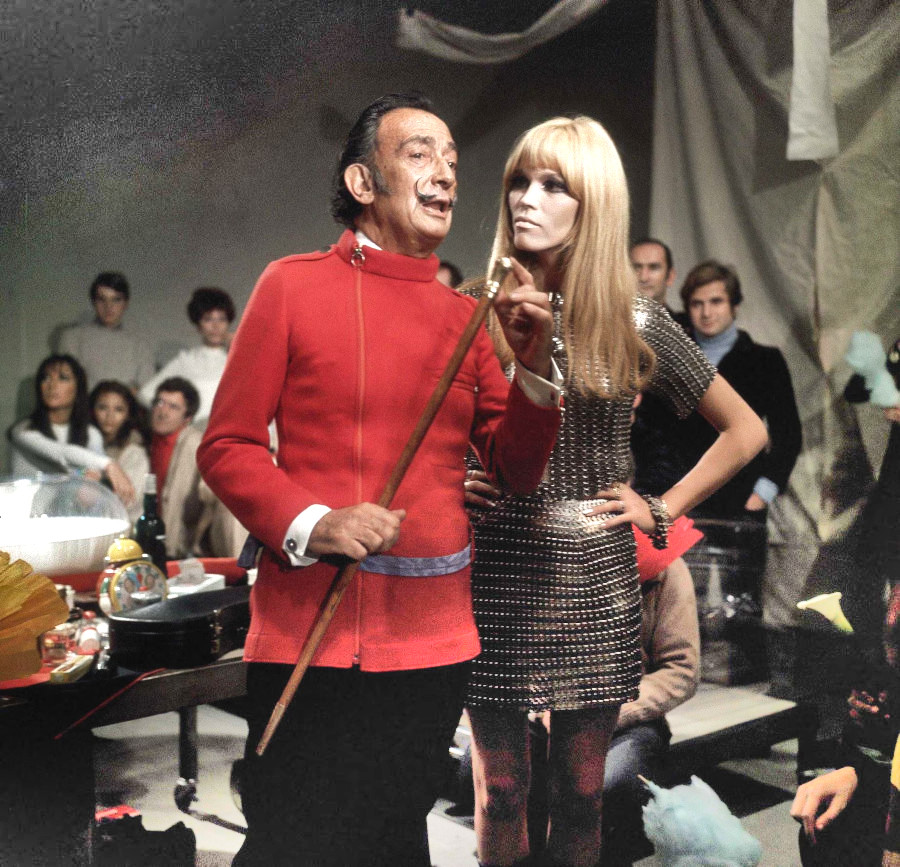

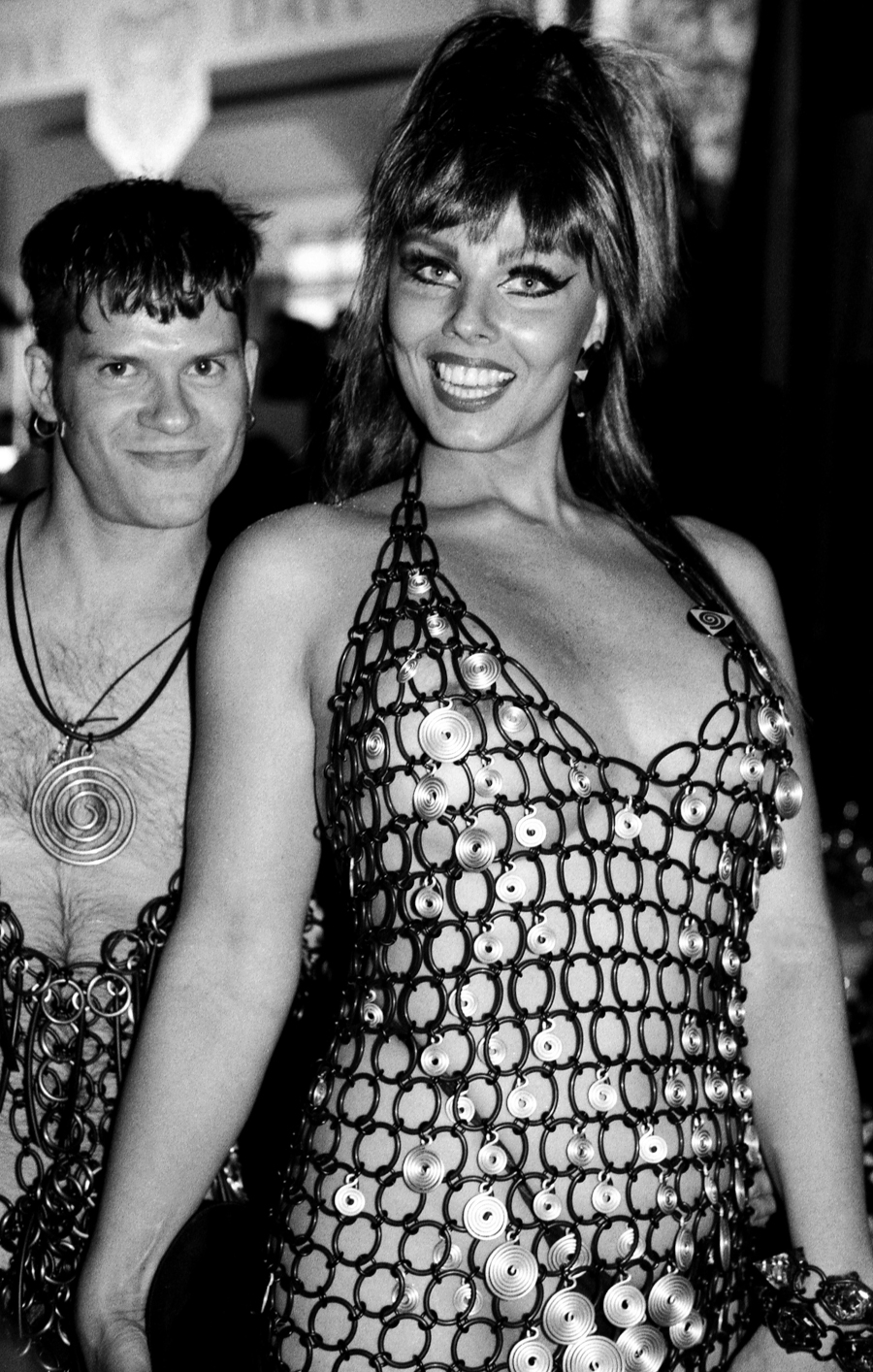

Then there was the breakout Peki d’Oslo (lately Amanda Lear), future Eurodisco diva, TV show hostess, a household name in Italy, who began rather than ended her public career modeling for the masses. In one of her earliest gigs, 1967, she showcased Yves’s tuxedo for women. In 1973 she was photographed with designer Mary Quant, whose mini was the defining ready-to-wear of the period. Amanda was its great adherent; “We went everywhere for the miniskirt,” she recalled.101 It was “a miniskirt and boots” she wore to her first meeting with renowned eccentric Salvador Dalí,102 another of those model-loving old men who, as an artist, at least had an excuse. His friendship with Amanda was lifelong, and he painted her many times. Almost four decades older, he was a thread stitched to classical dandyism; his cane, by rumor, had belonged to Sarah Bernhardt.103 “You have to marry an aristocrat,”104 he advised, but Amanda, unlike April, no longer even saw the use.

Amanda Lear Gallery

These were big names, celebrities to at least a subculture, but the ready-to-wear blitz ran through any number of forgotten women. Ina Barton, “in the throes of a marathon sex transformation,”105 modeled the same live shows as April, but is remembered only by April’s recollection. For her middle name, Ina chose Antoinette.106 In 1972 there was Pascal Barbner, Parisian, aged 23. By day, she modeled rtw, photoed for Vogue; by night, she performed burlesque, stating dryly in her only interview, “I am a transsexual.”107 Of course, not every model in this nouveau flood was trans – more were prostitutes – but by ‘78, the trans model was sufficiently typed that Andrew Holleran’s post-Stonewall classic of gay literature, Dancer from the Dance, drew her an insensitive portrait as “Lavalava, a Haitian boy who modeled for Vogue till an editor saw him in the dressing room with an enormous penis where a vagina should have been.”108 Scruples were forgotten, traditions slackened; borders to the demimonde were broached with fading caution.

Of course Yves, Mary, Elsa, the photographers, the hairdressers, the visagistes, they all knew. They had an idea. There was an ambient notion. “Modelling London knew,” April caged, “to some degree.”109 The adolescence of Amanda Lear, lone member of this cabaret clique to model ‘60s Saint-Laurent, is debated to this day with uncertainty. Yves himself based his first ready-to-wear collection on screenprints of his American bud, Andy Warhol, who retained various trans women circulating his art studio. One of these women, Potassa de Lafayette110 – Dominican, but her name, royalement français – had come up through the ballroom scene of the late 1960s;111 when Yves made rounds of New York nightclubs during stateside business ventures in ‘78, as expected, Potassa appeared for camera, gabbing his ear off. She modeled semiprofessionally, and remembered working the YSL line before;112 obviously, and much more forwardly, she wished to work it again.

Her idea was entertained, not embraced. Their mutual friend, American designer Halston, capably summarized views of fashion as a business: “I don’t make clothes for drag queens.”113 Successful adapters from the old school, only halfway in the halfworld, regarded themselves as transforming what women wore, not what they were. “Yves’s transvestites” were meant to be just that.

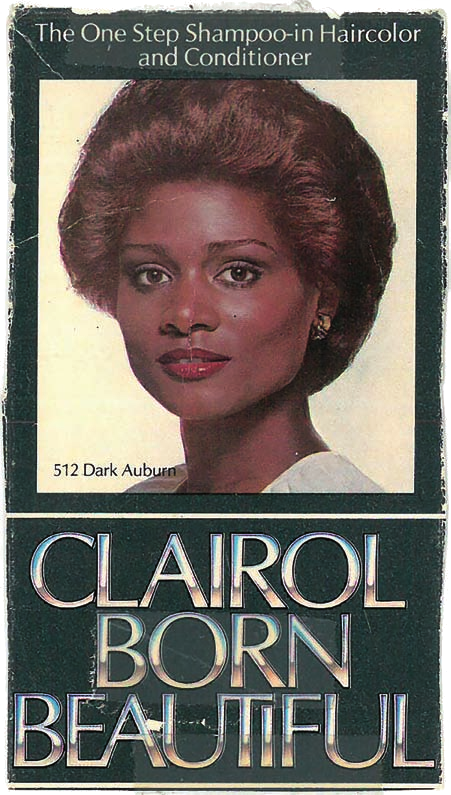

While practice demonstrated impossibility of this separation, marketing insisted. It would be tedious to compile every such reaction the fashion industry produced against its own insinuations, that we call discrimination, which is really synecdoche for the entire bourgeois state. “Jobs would unaccountably be canceled,” April summarized.114 Every trans model, every poor model, every Black model had a story.115 In 1980 Tracey Africa, another early ballroom child who slid into the industry, was outed on set for Essence magazine, and lost her six-year contract with Clairol. “Beauty and fashion is all about illusion,” she maintained, “so when the doors were opened for me, I walked right through. And then the doors slammed.”116 In a telling response, Tracey moved to Paris.

There was comic irony how discrimination was realized less often by Parisian tastemakers than mass manufacture, since it had all the jobs. To downmarketers, the idea of trans models was both too vulgar and not vulgar enough: a transsexual should neither be their everywoman, nor solicit her fantasies. Still a halfworld apart, she was, even Halston granted, “a bit off-putting for my clients.”117

The next generation of designers would view her, with themselves, differently. They were not hautes couturiers, technically; for decades that syndicate, down on rtw, denied them admission. Yet they were hardly megabrands either, rather auteurs, closer to boutiquiers like Halston or Quant, but more ambitious, literally “bigger than boutiques.”118 Named for the trade show debuting many of their collections, the “industrial creators”119 simply refused these distinctions. “The line between couture and ready-to-wear has been blurred,” Thierry Mugler would say.120 To be blurred was to be “better than couture.”121

Shy at first, bad boys on the edge of haute couture gradually foregrounded the demimonde in their public image. Restated bluntly, foreground withered away. “Fashion passed to the courtesan,” affirmed Mugler, asked once about “the rise of the bourgeoisie.”122 Already an industrial afterparty in 1978 with his Japanese coconspirator, Issey Miyake, employed two very public transvestites. The pack junior, Jean-Paul Gaultier, knowingly copied looks as a teen from filmed cabaret on latenight television. And however inconvenient, there were bad girls too: most notoriously a fellow traveler across the channel, Vivienne Westwood, who was herself a parvenue. Her boutique, tellingly renamed from “SEX” to “Seditionaries,” employed sex workers part-time.

From America, at once liberated yet provincial for its national crack in the aristocratic imaginary, more advanced inversion erupted in impermanent spurts. Straight to the point, designer Patricia Field simply fathered a ballroom house herself (House of Field, ‘87). Jeweler David Spada consciously did make clothes for drag queens, taking measurements during house calls with trans nightlife entertainer International Chrysis circa 1983.123 His cone bra for her antedated Gaultier’s runway cones by roughly a year.124 Stephen Sprouse got called an American Gaultier, but just as well prefigured him too: his 1984 debut show included men in skirts a full year before Jean-Paul made it his brand. To open that debut, however, he demanded not a man, but his fit model and, shockingly, good friend Teri Toye, who was a few years into transition. “It was never a goal of mine to become a model,” said Teri. “I had to do it.”125 On the runway, she stripped off an expensive, handstitched jacket and, over and over, smashed it on the ground.

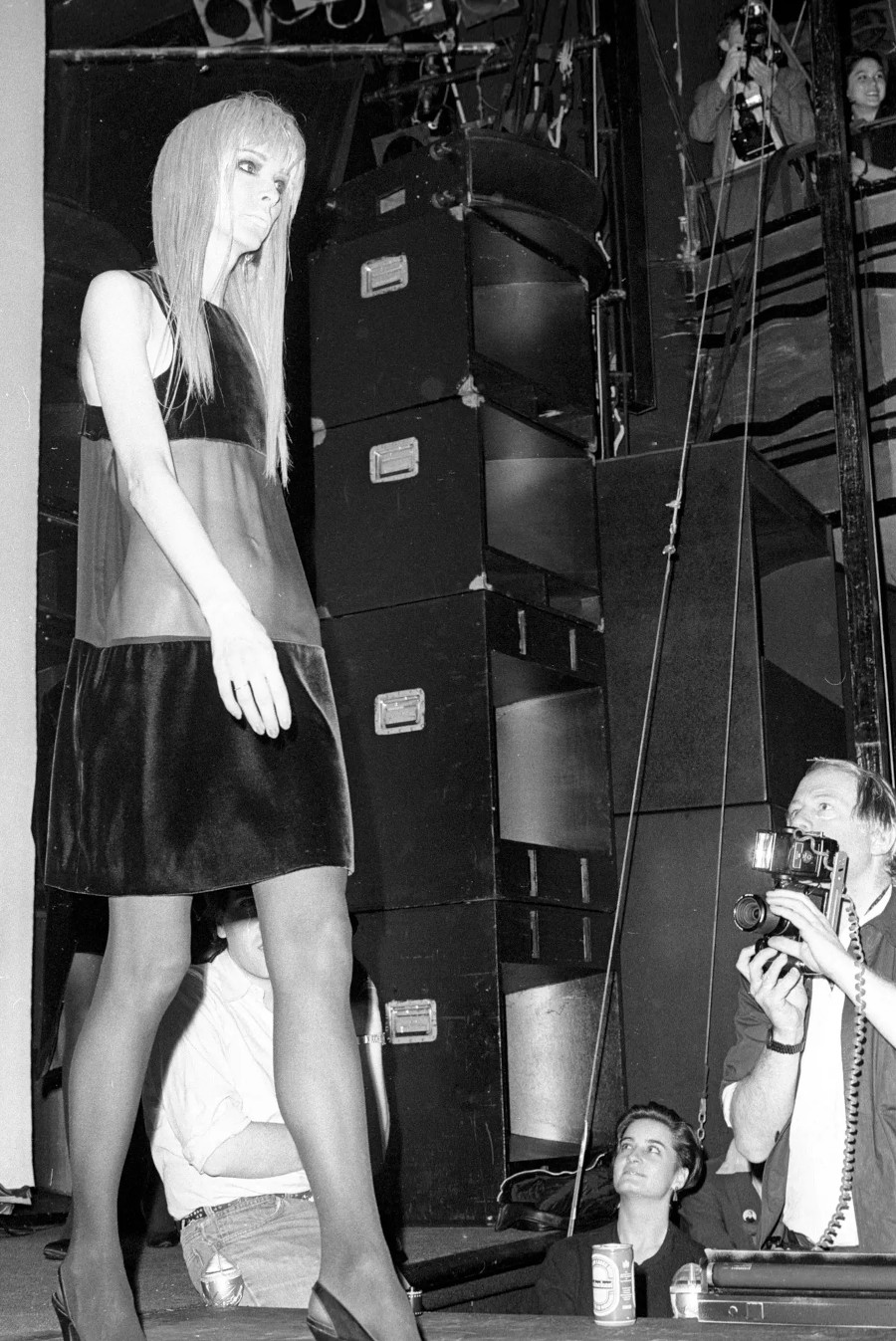

All this was punk business. “They used to consider us punk rock,” Pat Field remembered, “and I was like, ‘punk rock’? Okay, punk rock.”126 Music on Sprouse runways was Iggy Pop, Souixsie and the Banshees. Gaultier cropped and bleached his hair, platinum blonde. They did not have the first transgender model on their hands, but the mood was right to insist on it. Across three hot years Teri posed for a doll by Greer Lankton (also transsexual), a “wraithlike”127 portrait by Carl Apfelschnitt (since lost), photos from Kate Simon and Nan Goldin, and sure enough, picked up international work modeling Mugler, Gaultier, and Vivienne Westwood, in that order.128 At the Gaultier show, newsies reported she made “obscene gestures at the audience”129: punk behavior.

Teri Toye Gallery

Within this fashionable subspecies of punk was a cool elaboration on dandy theory. London press literally called some “new dandies,”130 forgetting “punk” was already slang for sodomite. In Nan’s photo Teri lies in bed with her husband, reading Baudelaire. More crassly, the bouncer outside one of her early nightclub haunts remembered “never a boy Teri Toye” wearing a tiara to sit upon her “throne,” that is, a unisex toilet.131 Mugler, once questioned directly about Baudelaire’s philosophy, found himself agreeing with everything but disdain for nature:

“Exactly. We have to be frank… The minute you put on clothes, this is an act of civilization. So I don’t believe in natural fashion, either… What I was saying in my choice of models is that this game of femininity, if you choose to play it – well, why not a transsexual? Because they are the maximum.”132

Mugler said this in 1994. His sentiments were publicized a few years after American peers, but across the ‘90s, he alone possessed means and ends to carry them to, in his phrasing, “the maximum.”

Adrian Magnifique, of the House of Magnifique (whose father was “Punk Rock Frankie”), remembered the phone call.

“‘You have to come to The Tunnel [nightclub]. Thierry’s doing an audition. He’s looking for dancers, voguers, to take to his show in Paris’… we got there and all the houses, from Ebony, Xtravaganza, LaBeija, they were there, ready to audition for the runway show in Paris.”133

His friend, Willi Ninja, had just been sniped at the ‘88 House of Field ball,134 which Patricia had stuffed with a twelve-judge panel of high fashion bigwigs.135 To compete alongside ballroom children, she invited literal supermodels.136 They had found their moment.

If Mugler did not hire a femme queen that evening, that was because, at least in part, he already had one in mind. The several names of Connie Field, Connie Girl, Connie Fleming, had been dancing across the tongues of his employees from New York for months. Lacking the name, one photographer simply demanded, “Find that whore.”137 At the next of these retrofitted138 industry balls, the 1989 AIDS Love fundraiser, Connie was a contestant, modeling her usual smallball game; but Mugler was a judge. “Oh,” he responded, after she was ushered to him backstage, “now I get it.”139

“It was like a fever dream,” Connie remembered.140 She knew the history, had the walk: her mentor Chrysis namedropped Potassa, Tracey Africa, and gifted her April Ashley’s autobiography;141 she “idolized” Teri Toye, believing “her style was effortless”;142 she even bandied about theoretical jargon like “the democratization of fashion.”143 “I kind of flew under the radar the first two seasons,” she remembered, “and then my history started to sort of be known… I wasn’t hiding from it… I wasn’t going to be made ashamed of the community that rebuilt me…”144

There was no obligation to hide. The frantic queer paradise of the Mugler backstage in those years has scarcely ever been appreciated, and never documented, in full. High elder Amanda Lear returned to catwalk ‘90 and ‘95; Bibiana Fernández, a Spanish transsexual who recorded dandy punk in La Movida, walked ‘92; “That first season for Mugler,” Connie added, “1990, there was another out trans woman, Latina. I can’t remember her name.”145 Who was she? Runways swamped with New York dragsters, old friends of Connie like Zaldy, Lypsinka, Joey Arias. One male model discovered via Westwood, not even big on drag, embraced the occasion to walk the female line.146

It was not just Mugler, although he was grandiose. A million little hautes coutures were blooming through the cracks. In Italy, designer Chiara Boni went so far as to rent out a gay cinema for an entire runway “con solo trans.”147 Starring in her ‘95 show was Eva Robin’s, a backup dancer to Amanda Lear, whose full frontals for Playmen magazine had been labeled, in an absurd euphemism, “sexually ambiguous.”148 Surrounding seasons, stars were actresses from hardcore pornography.149 In Spain, designer Francis Montesinos invited ballroom child Carmen to walk ‘96 Cibeles Madrid;150 she established a considerable modeling career there, her home country, before returning stateside to mother the House of Xtravaganza. In Brazil, model Roberta Close, who got her start posing topless for girlie mags, turned to local designer Clodovil Hernandes;151 by ‘91, she turned the Mugler catwalk. “It was the first time I felt like a complete woman,” she wrote.

“Parading alongside those marvelous top models – Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, and Naomi Campbell – who were completely unaware of my history and treated me as equal, I realized that if I wanted, I could turn my dream into reality. And I began to think seriously about a sex-change operation.”152

Across Japan, southeast Asia, wherever yet another globalized “fashion week” shot up, some biding trans women shot up under it.153

If such sudden exposure seemed part of a fad, it was. “There was a moment in fashion where drag was pushed,” Connie specified, “…and I was like, okay, this was my past, but I am trans. And that was sort of put to the side.”154 From outside peeking in, it remained more revelatory, for models like Roberta, to not be recognized as transgender in the wider sense, even as they benefited in the wider recognition. This dual aspect of trans psychology is our private iteration of the general social paradox of our day.

As for the public iteration, conveniently, Mugler retired in 2002, just weeks before majority shareholders in his business declared its fiscal year “unacceptable.” Losses totaled over twenty million dollars. The artist could not be reached for comment,155 but years later, he alluded, “…we did it without much money,” and “I think now it’s the money who tells the artist what to do – it’s not the artist who tells the money what to do.”156 While younger agitants, Gaultier especially, persisted in light mischief, the lion’s downfall was felt. Bourgeois society has been a temperamental master.

So when our few famous trans models today collect their icons, they hardly mind the millennium. They mind 1989. Laverne Cox rents a whole second apartment as a “museum slash closet” to display her Mugler collection, over five hundred pieces from the era.157 Hunter Schafer frames a movie poster for 1990 ballroom documentary Paris is Burning in her home.158 Alex Consani cites her favorite model as Connie Fleming.159 Among contemporary femme queens, several big breakouts were achieved, in concerning repetition, by being cast in Pose, a televised period piece for those breakout years of ballroom. Anticipating downfall, we all gaze back at the year of the flood.

And as for me? Petite vieille moi? Tradition dictates, at the end of a runway, that the artist briefly reveal herself. Granted, I am no artist, no designer, no model. Attentive readers may be unsurprised to learn I am not fashionable at all. Since writing, however, I have begun to reconsider. Visiting luxury boutiques, I feel the fabric. I eye the cameras. I reflect once more, and ever deeper, on potential uses of the revolutionary guillotine.

□

0A. Media Bibliography

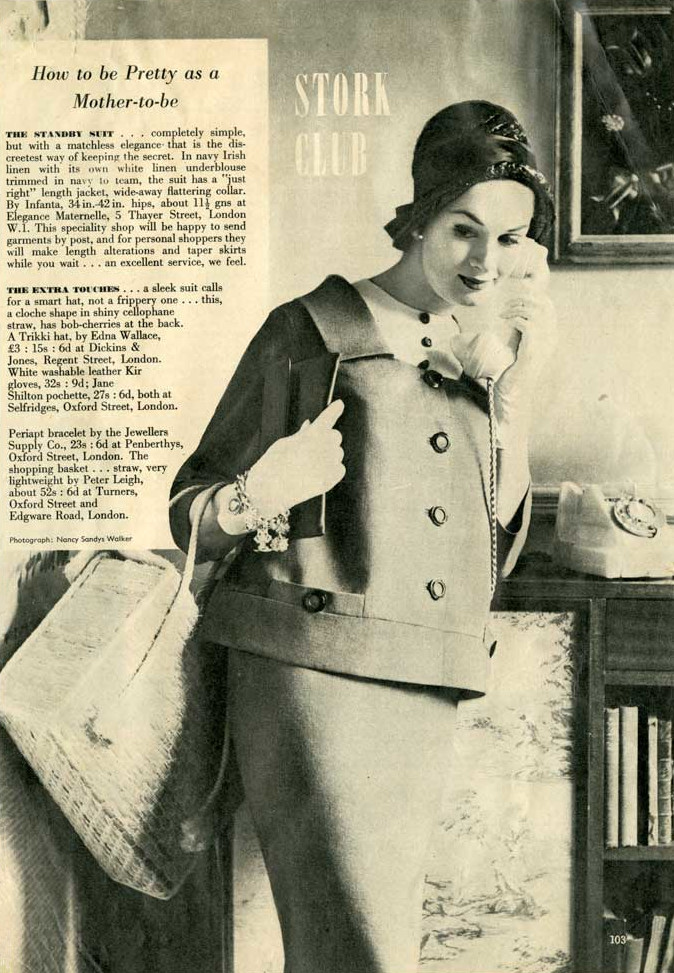

Fashion history is a history of images; modern fashion history is a history of proprietary images. The author insists all images and video clips in this essay have been obtained and distributed under fair use. Nonetheless, wherever possible, obvious, and accessible I have inquired with rightsholders beforehand and included the image to their specification. In that vein the media bibliography will precede all other commentary. Image numberings run left to right.

1.1 – Painter: Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Model: Eugénie de Montijo. Title: The Empress Eugénie (sometimes The Empress Eugénie as Marie-Antoinette). Image Source: website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Misc: Apparently derived from a photograph, of unclear origin, which has circulated the internet for some years. See for instance L'Impératrice costumée on Gods and Foolish Grandeur blog, March 23, 2018.

1.2 – Photographer: likely James Lafayette. Model: Frances Evelyn “Daisy” Greville. Dressmaker: likely Jean-Philippe Worth. Image Source: The Lafayette Negative Archive. Misc: Image source webpage includes a wealth of further citational material. Great thanks to Russell Harris for maintenance of this excellent archive.

1.3 – Photographer: Félix Nadar. Model: Andrée Worth. Image Source: Librairie Diktats.

2.1 – Image Source: The Opulent Era by Elizabeth Ann Coleman, pg. 139. Misc: My image scan is poor. The image appeared earlier in Mystère et splendeurs de Jacque Doucet (1984) by François Chapon.

2.2 – Image Source: The House of Worth 1858-1954: Birth of Haute Couture by Chantal Trubert-Tollu et al., pg. 24.

3.1 – Painter: Henry Bone. Model: Elizabeth Tudor. Image Source: Bonhams auction website.

3.2 – Image Source: The House of Worth 1858-1954: Birth of Haute Couture by Chantal Trubert-Tollu et al., pg. 19.

4.1 – Photographer: likely James Lafayette. Model: Lillie Langtry. Image Source: The Lafayette Negative Archive. Misc: Image source webpage includes a wealth of further citational material.

4.2 – Photographer: Henri Manuel. Model: Sarah Bernhardt. Image Source: Bibliothèque Nationale de France Gallica.

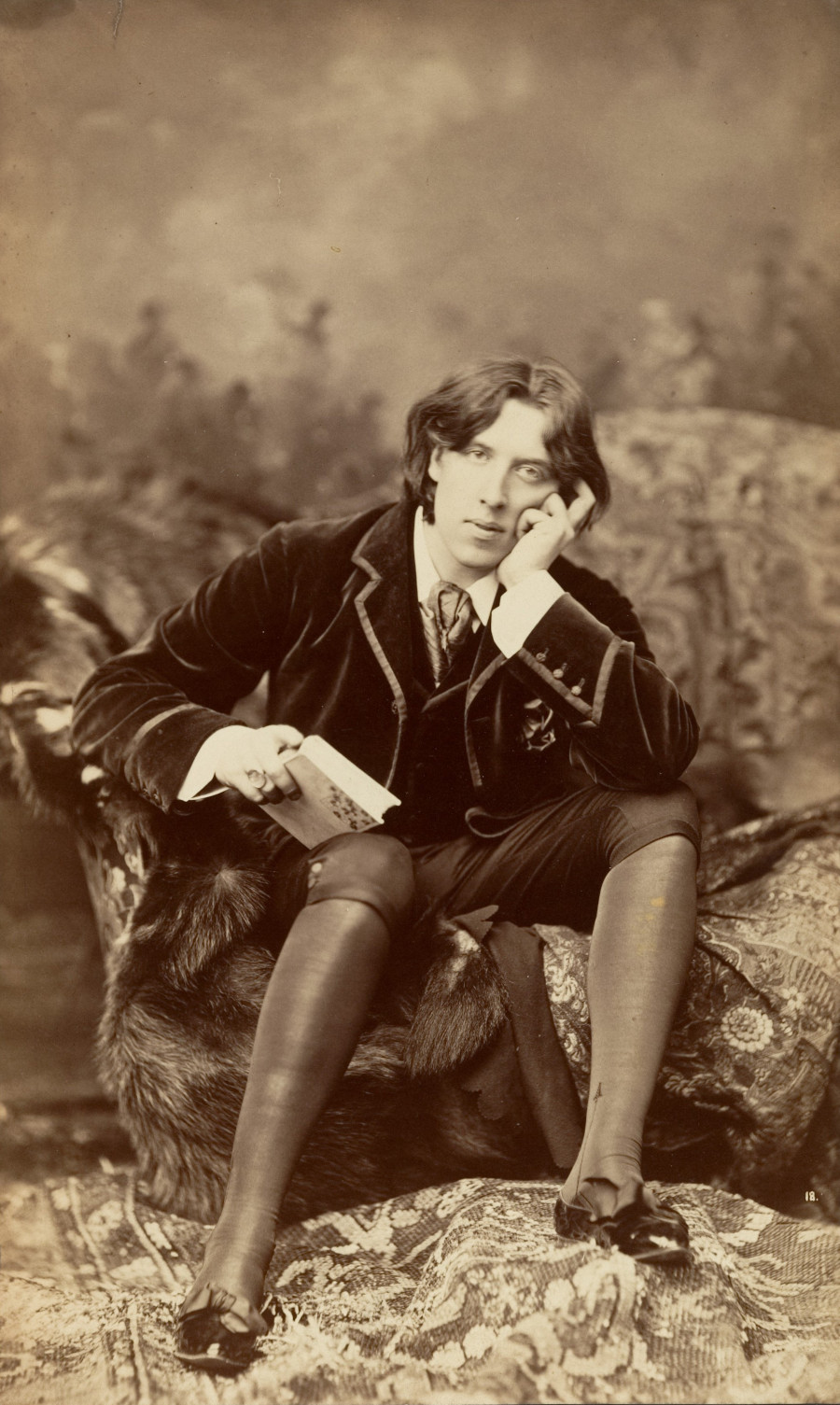

5.1: – Photographer: Napoleon Sarony. Model: Oscar Wilde. Image Source: Oscar Wilde in America website. Misc: Great thanks to John Cooper for research and website maintenance.

5.2: – Painter: Giorgione. Title: Sleeping Venus. Image Source: Google Art Project.

6.1: – Photographer: Julien Vidal. Copyright: Julien Vidal, Galliera, Roger-Viollet. Dressmaker: Charles or Jean-Philippe Worth. Image Source: Exhibition on Countess Greffulhe webpage.

7.1: – Painter: Jean-Laurent Mosnier. Model: Charlotte d’Eon. Image Source: webpage. Misc: I have contrast-adjusted the image slightly. The National Portrait Gallery has popularized the imitation by Thomas Stewart identified in 2011. This original still circulates, but I could not identify its origin.

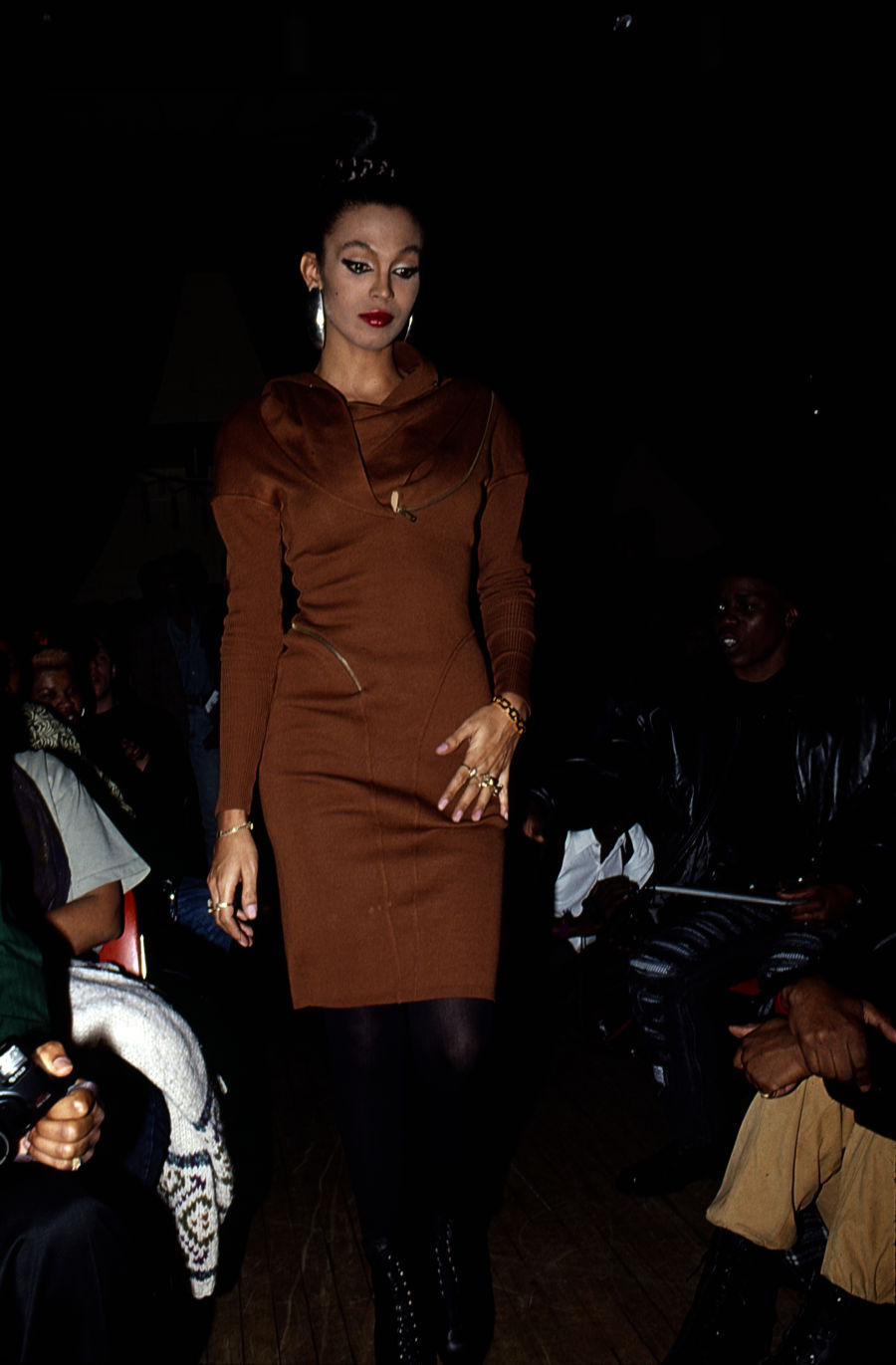

8.1: – Photographer: Chantal Regnault. Models: Danielle Revlon and Jerome LaBeija. Image Source: Personal communication. The image also appears with Chantal’s collected ballroom photos in Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92 (2011), pg. 67.

8.2: – Photographer: Chantal Regnault. Model: Carmen Xtravaganza. Designer: Azzedine Alaia. Image Source: Personal communication. The image also appears cropped on Chantal’s Instagram.

9.1: – Directors: Michele Capozzi and Simone de Bagno. Model: Shamecca (Beverly Ash). Video Source: T.V. Transvestite, uploaded to YouTube by Wolfgang Busch.

9.2: – Subject: Venus Xtravaganza. Image Source: “Paris is Burning” by Martina Randles for Dazed digital, April 24, 2009.

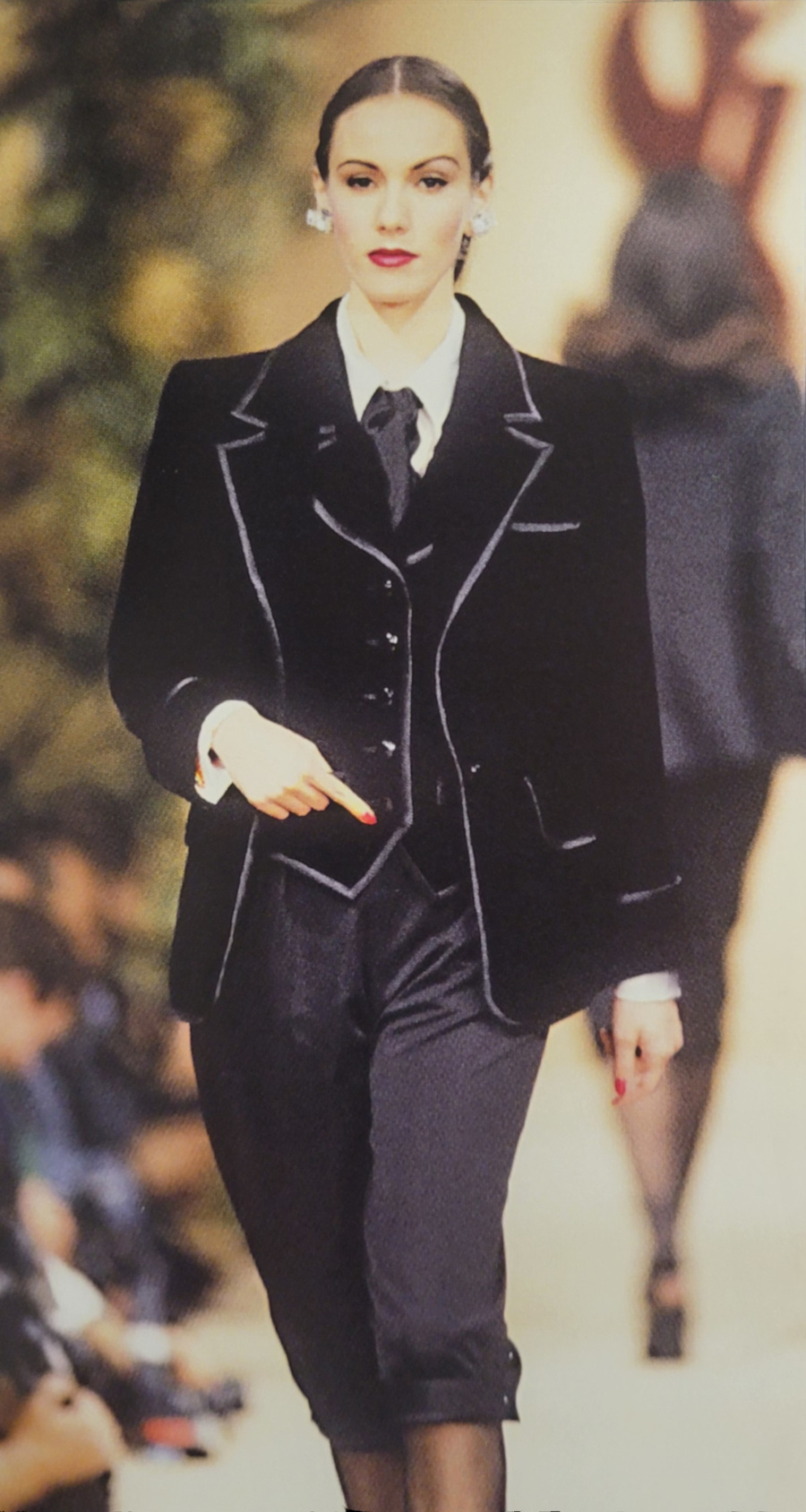

10.1.1: – Designer: Yves Saint-Laurent. Image Source: Yves Saint Laurent Catwalk: The Complete Haute Couture Collections (2019), publisher Thames & Hudson, pg. 479.

10.1.2: – Photographer: Napoleon Sarony. Subject: Oscar Wilde. Image Source: Oscar Wilde in America website.

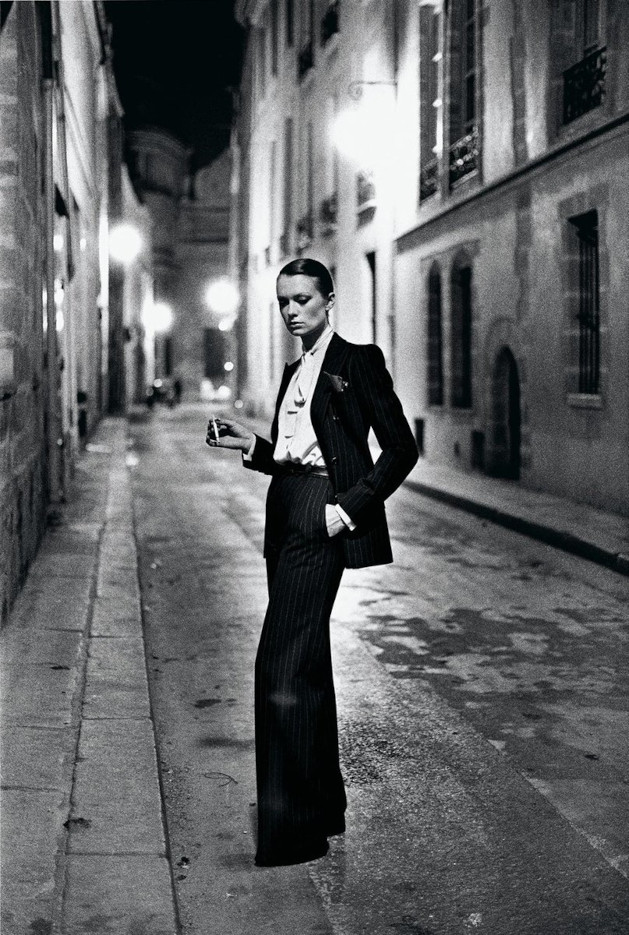

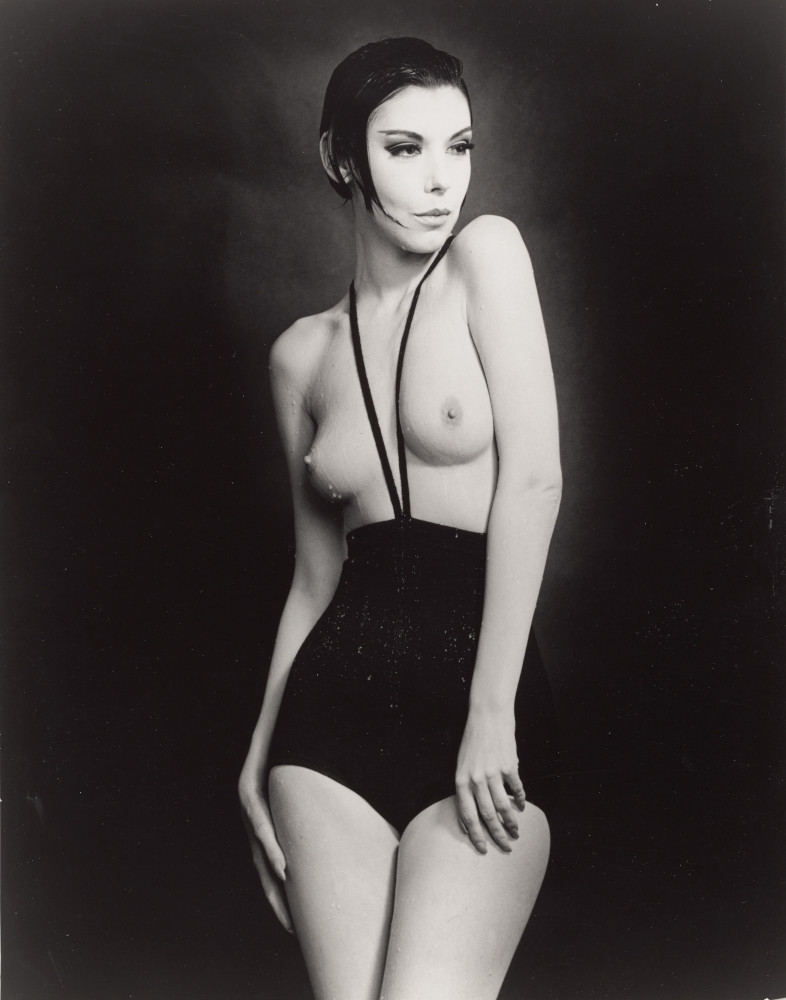

10.2.1-3: – Photographer. Helmut Newton. Models: Vibeke Knudsen. The nude model could not be located. Designer: Yves Saint-Laurent. Image Source: Lot images at Christie’s.

10.3.1: – Photographer: Horst P. Horst. Image Source: “Yves Saint Laurent’s Château Gabriel: A Passion for Style,” Vogue, December 1983, pg. 302.

10.3.2: – Photographer: David Bailey. Model: Jean Shrimpton. Designer: Yves Saint-Laurent. Image Source: “The Paris Look” in Vogue September 15, 1971, pg. 70-71.

10.3.3: – Image Source: Toby Üpson blogpost, which cites Vogue Paris, November 1971, pg. 19. Misc: Photo edited for shadow removal.

11.1: – Photographer: David Bailey. Model: April Ashley. Image Source: “Born Beautiful” by Mikelle Street for out.com. Misc: This image has been passed around for years, with best citation British Vogue 1960 or 1961. Specifics elude.

11.2: – Photographer: David Bailey. Model: April Ashley. Image Source: April Ashley’s Odyssey, photo insert between pgs. 184-5. Misc: April provides the photo appeared in Sunday Times, 1969.

11.3: – Model: April Ashley. Image Source: “April Ashley: her early life” blogpost by Vicky Iglikowski-Broad for The National Archives, March 31, 2023.

12.1: – Model: April Ashley and Marie Pierre-Pruvot. Image Source: “April Ashley - Portrait of a Lady - Video Slideshow” on Youtube. Misc: April included the photo, with a second, rarer picture in her second autobiography, The First Lady.

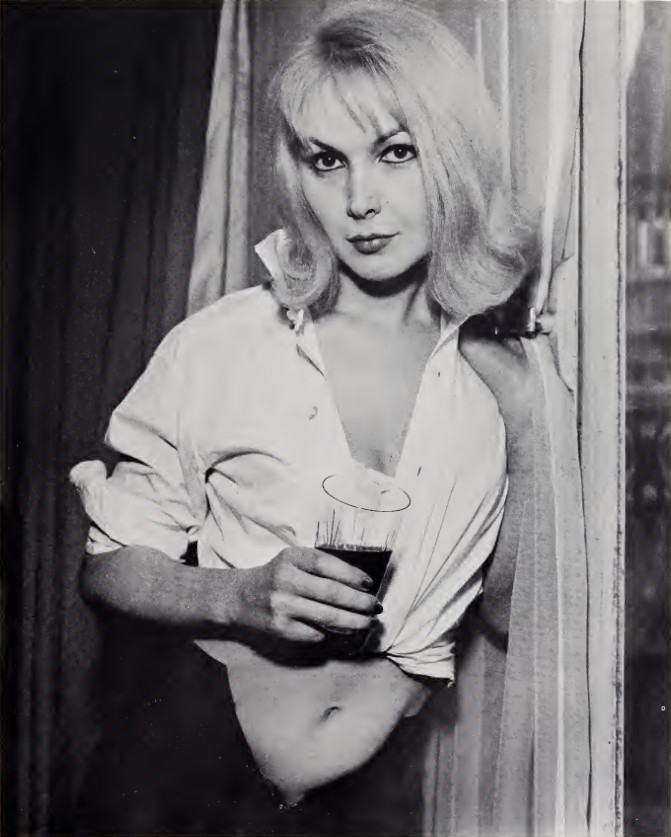

12.2: – Model: Marie Pierre-Pruvot. Image Source: Female Mimics, v.1 nr. 5, pg. 43.

12.3: – Photographer: David Marie-Louise. Model: Marie Pierre-Pruvot. Maquillade and Hair: Stéphane Israel. Designer: Mathieu Matachaga. Image Source: Marie’s website.

13.1.1: – Photographer: Gunnar Larsen. Model: Amanda Lear. Designer: Yves Saint-Laurent. Image Source: Amanda Lear official Facebook. Misc: See also commentary from Amanda on Instagram.

13.1.2: – Photographer: Terence Donovan. Model: Alexander Plunkett-Greene, Amanda Lear, Mary Quant. Designer: Mary Quant. Image Source: Liz Eggleston blog. Misc: My great thanks to Alex at the Terence Donovan Archive for alerting me to this picture, and sending me the article.

13.2.1: – Model: Salvador Dalí, Amanda Lear. Copyright: Sipa/Shutterstock. Image Source: “The Surreal Influence on Gender & the Art of Drag” by Kayla Dorsey for The Dalí Museum online. Misc: I have brightened the photo.

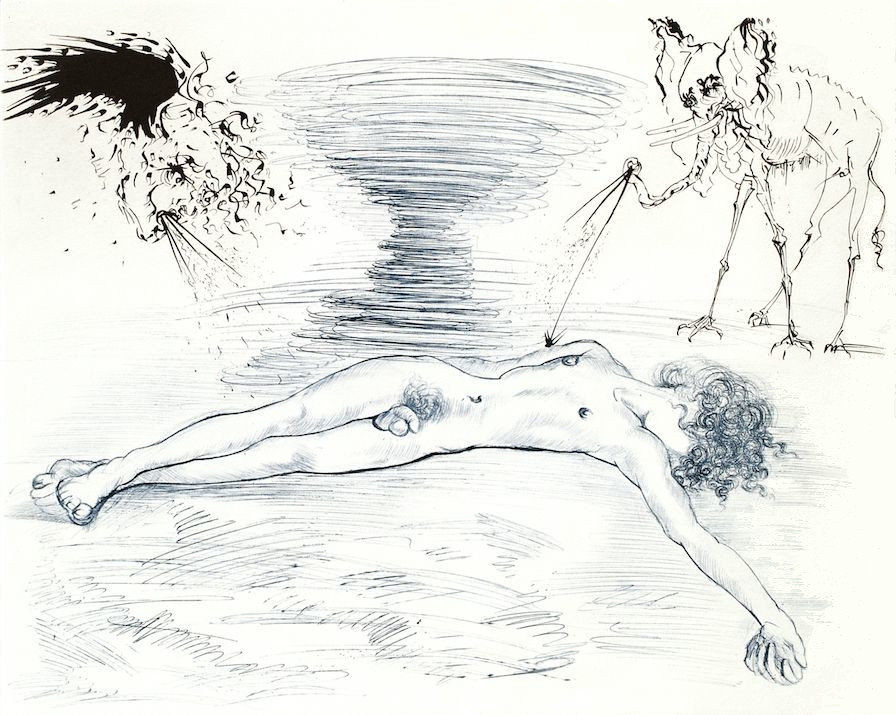

13.2.2: – Painter: Salvador Dalí. Title: Hypnos. Image Source: Off the Wall gallery.

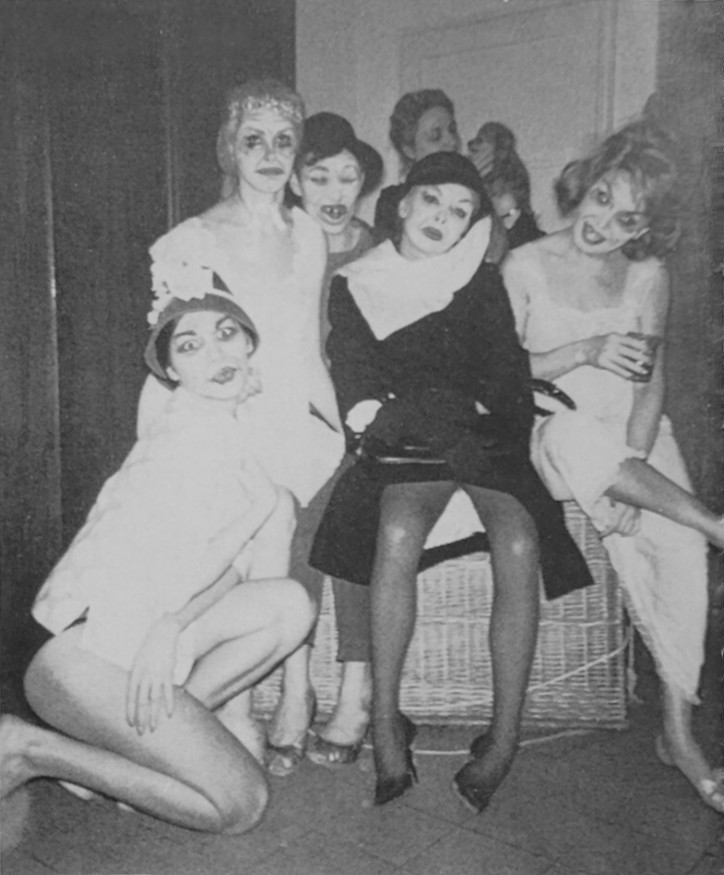

13.3.1: – Models: Amanda Lear, April Ashley, Novak, Coccinelle, Kiki Moustique. Image Source: April Ashley’s Odyssey, photo insert between pgs. 88-89.

13.3.2: – Photographer: David Bailey. Model: Amanda Lear. Image Source: Fashion Plate magazine interview with Amanda Lear. Misc: No exact date. I believe the image was provided from Amanda’s own collection.

14.1-3: – Photographer: Roger Picard. Model: Pascal Barbner. Image Source: “Les Reines de Paris” by G.Y. Dryansky in Women’s Wear Daily, June 29, 1972, pg. 4.

15.1.1: – Photographer: Sonia Moskowitz. Pictured: Halston, Loulou de la Falaise, Potassa, Yves St. Laurent, and Nan Kempner. Copyright: Getty Images. Image source: Getty Images. Misc: Getty has aggressive acquisition and litigation policies which have devastated use of images in modern history. Recently they have allowed legal embedded links for some of their images.

15.1.2: – Photographer: Andy Warhol. Pictured: Salvador Dalí and Potassa. Image Source: Reddit. Misc: This would appear to be a high quality render of a photo found on the Andy Warhol contact sheets at Stanford University.

15.2.1: – Model: Fred Hughes, Potassa. Hair: Eugene di Cinandrè, “John of Vidal Sasson.” Maquillage: Patrick Hourcade. Image Source: Vogue Italia, Feb 1972, pg. 16.

15.2.2: – Photographer: Sal Traina. Model: Potassa. Designer: Halston. Image Source: “Potassa – an epitome” in Women’s Wear Daily, September 4, 1974, pg. 14.

15.3.1: – Photographer: Antonio Lopez. Model: Potassa. Image Source: Daniel Cooney Fine Art

15.3.2: – Photographer: William Coupon. Model: Potassa. Series: Studio 54: Disco Tribes. Image Source: Another magazine, online.

15.3.3: – Photographer: Andy Warhol. Model: Potassa. Title: Drag Queen (Potassa de la Fayette). Image Source: Christie’s auction site.

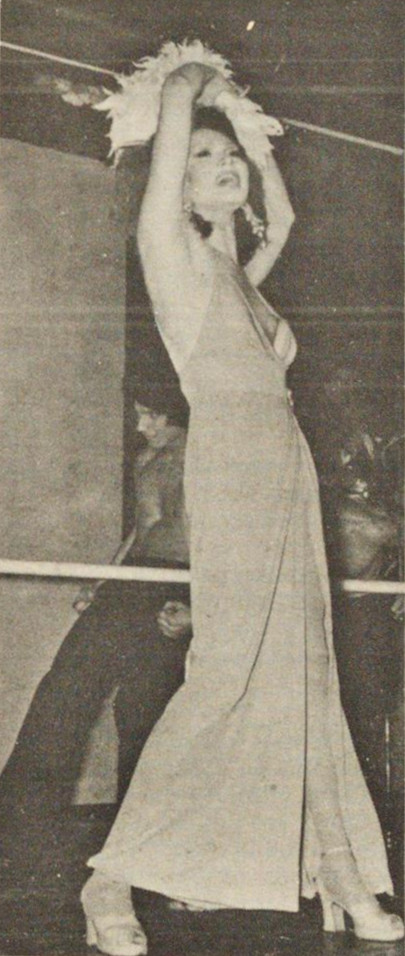

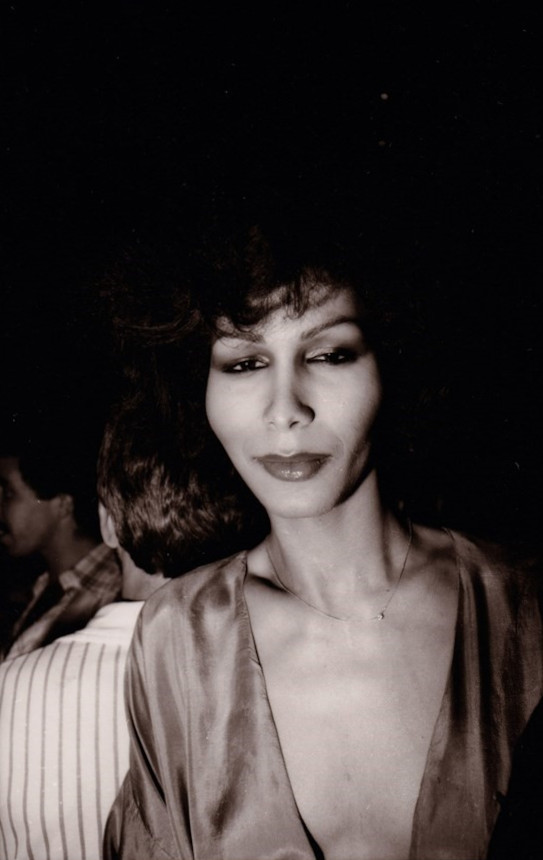

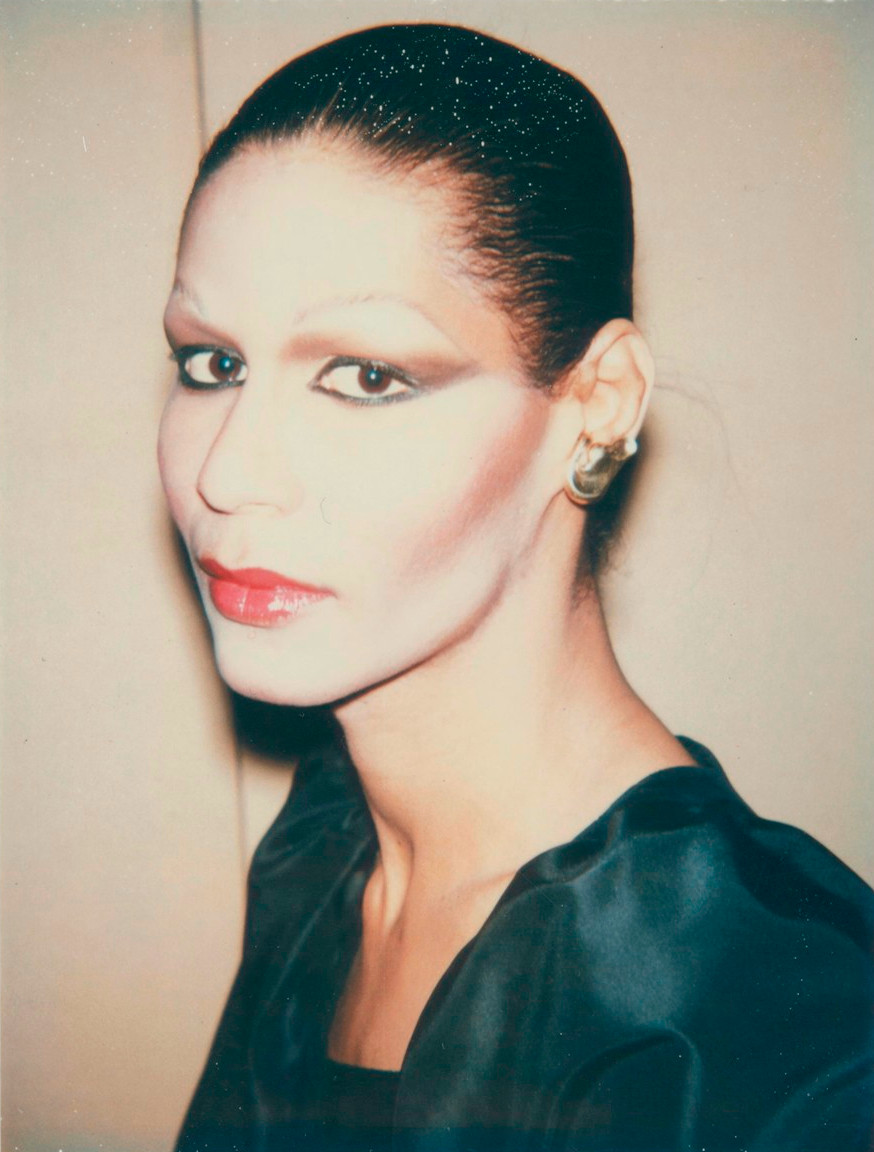

16.1: – Model: Tracey Norman. Image Source: Work!: A Queer History of Modeling by Elspeth H. Brown, pg. 3. Misc: This image was previously popularized in Tracey’s breakout story for The Cut.

16.2: – Model: Tracey Norman, others unknown. Image Source: “Tracey ‘Africa’ Norman, the 1st Black trans model, was born before her time” by Jillian Eugenios for Today online, June 1, 2021.

16.3: – Directors: Michele Capozzi and Simone de Bagno. Model: Tracey Africa (Tracey Norman). Video Source: T.V. Transvestite, uploaded to YouTube by Wolfgang Busch.

17.1: – Photographer: William Claxton. Copyright: The William Claxton Estate. Model: Peggy Moffitt. Designer: Rudi Gernreich. Image Source: The Getty Museum

17.2: – Directors: Michele Capozzi and Simone de Bagno. Model: “Lucille.” Video Source: T.V. Transvestite, uploaded to YouTube by Wolfgang Busch.

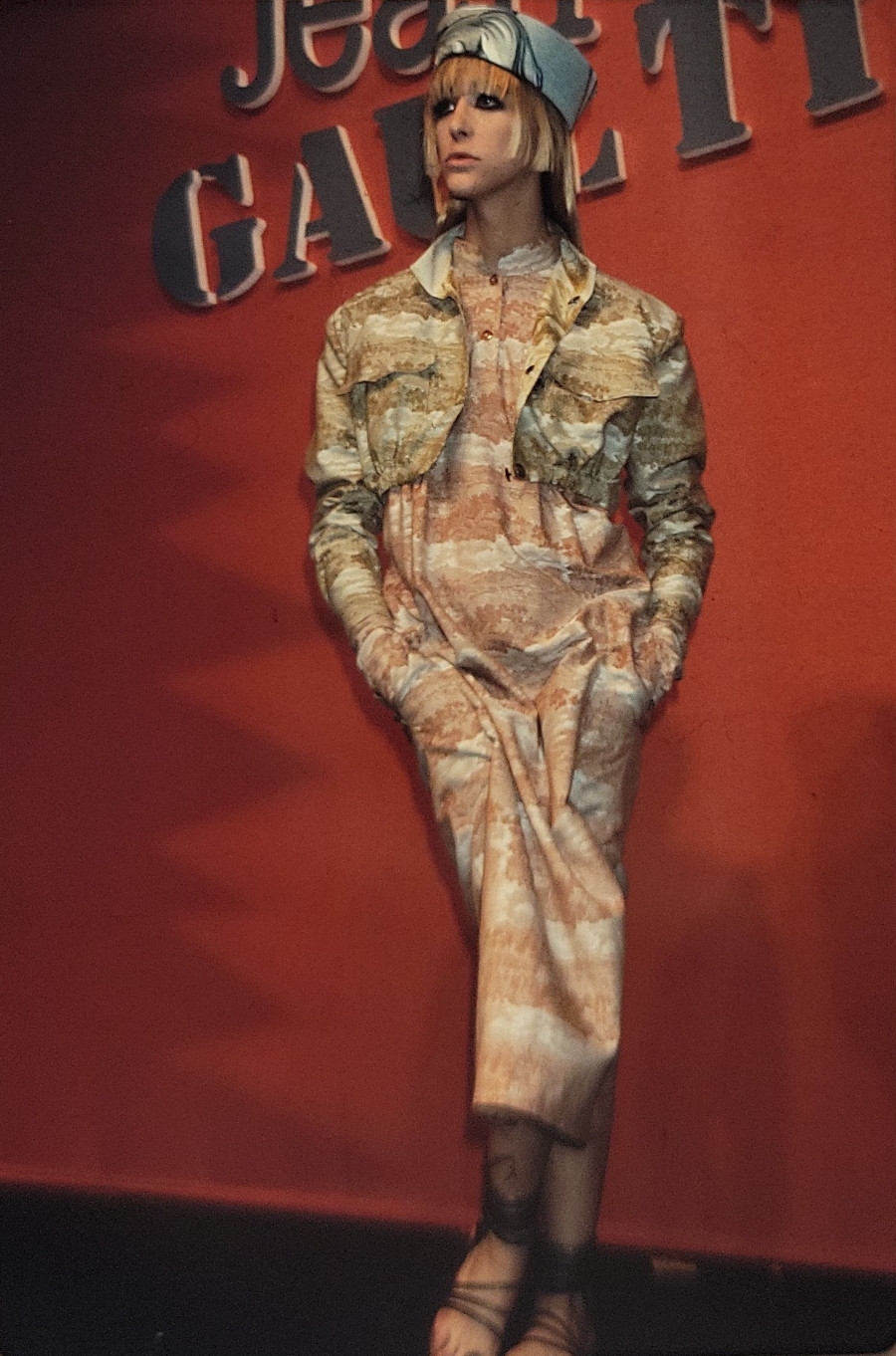

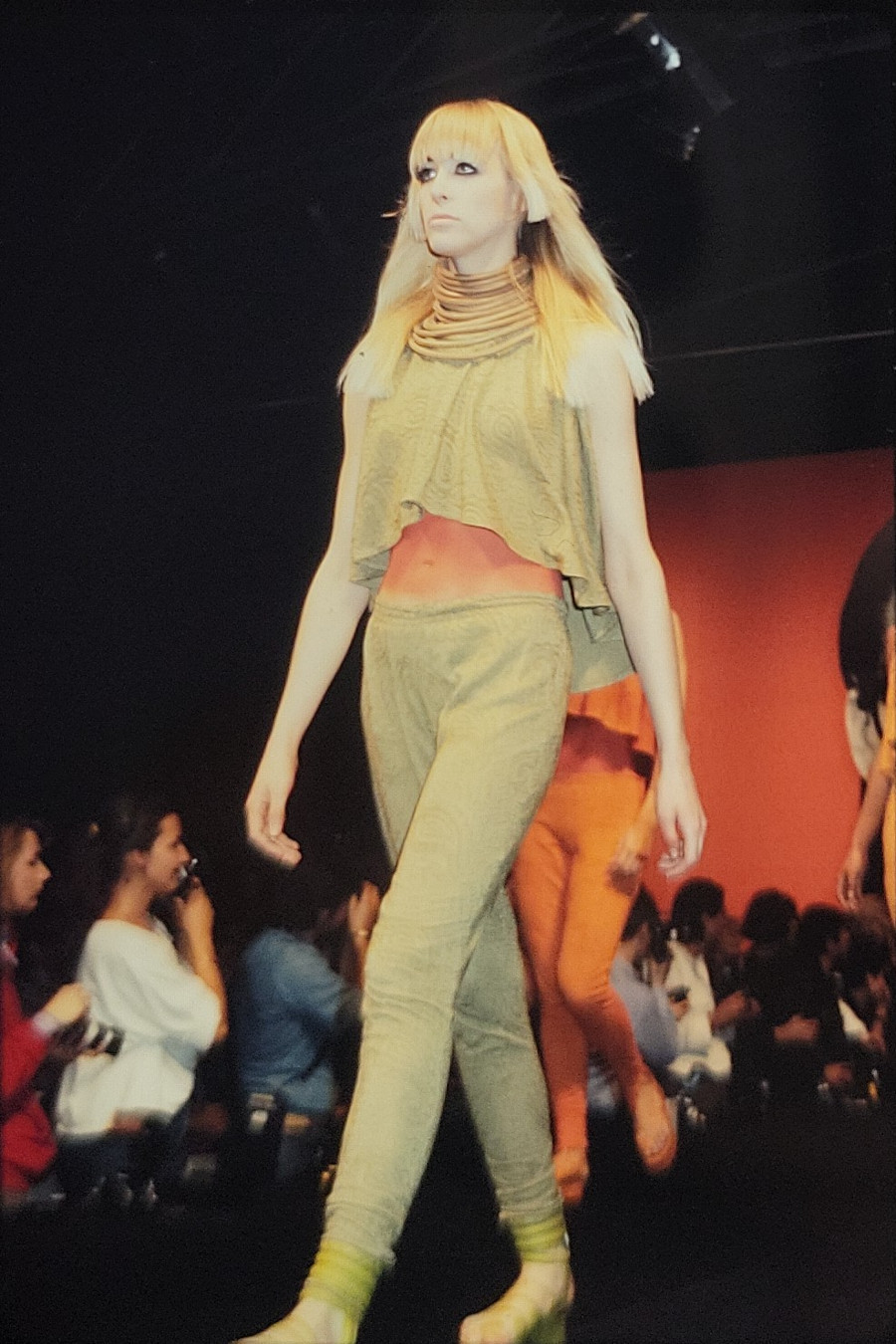

17.3: – Photographer: Peter L. Gould. Designer: Thierry Mugler. Image Source: Runway slides at Fashion Institute of Technology, US NNFIT SC.497.968, #1.

18.1-2: – Photographer: Ichiro Fukimara, James Magyer, or H. Kiyosawa. Image Source: “The Tokyo Six” in Women’s Wear Daily, December 4, 1978, pg. 7.

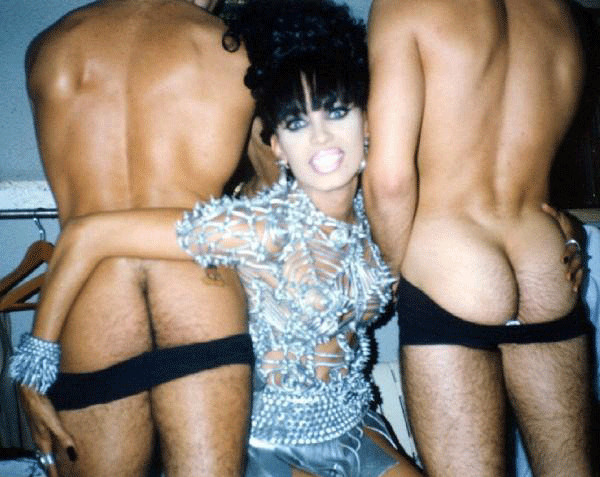

19.1.1: – Photographer: John Simone. Model: David Spada and International Chrysis. Designer: David Spada. Image Source: Personal communication with photographer, but see John Simone Photography website.

19.1.2: – Photographer: Frankie Chillino. Designer: David Spada. Image Source: puccilover eBay page

19.1.3: – Photographer; Jean Baptiste Mondino. Model: Madonna. Design: Jean-Paul Gaultier. Image Source: Harper’s Bazaar, June 1990. The image is shared widely, see ex. futurefriends.ny Instagram page.

19.2.1: – Model: International Chrysis. Designer: Joey Gabriel. Music: Malcolm McDowell. Video Source: House of Field ‘88 ball on YouTube. Misc: See also the documentary Love is in the Legend by ball MC Princess Myra Lewis.

19.2.2: – Model: Salvador Dalí, International Chrysis. Image Source: See Crossdreamers interview with Zagria. Misc: Appears in promotional materials for Chrysis documentary Split: Portrait of a Drag Queen.

20.1.1: – Photographer: Kate Simon. Model: Teri Toye. Dollmaker: Greer Lankton. Image Source: Kate Simon Instagram page.

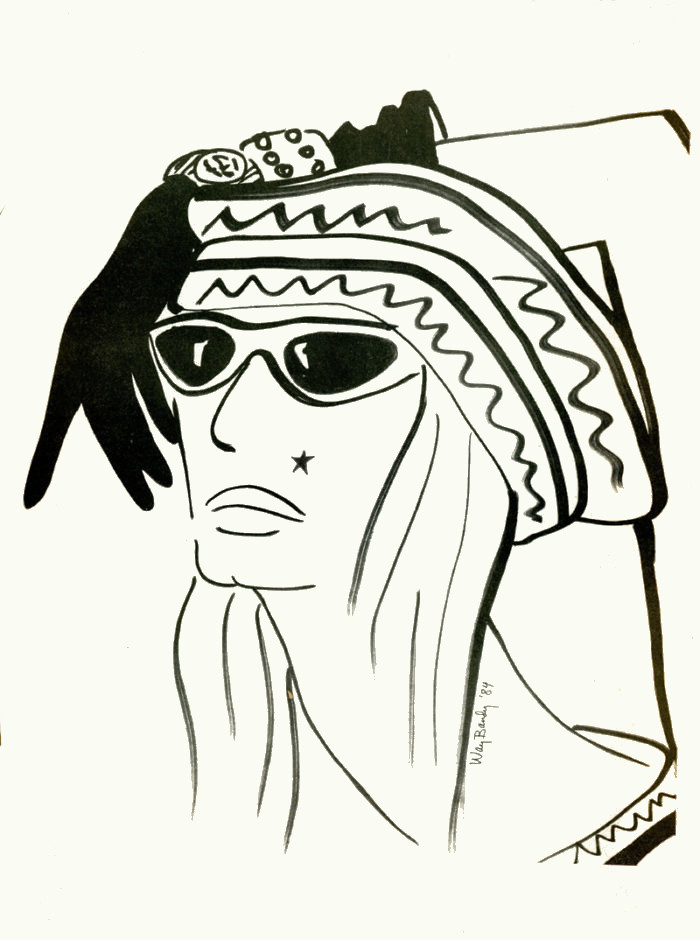

20.1.2: – Artist: Way Bandy. Model: Teri Toye. Image Source: Details magazine, June 1984. Scans hosted at Gallery 98. Misc: I have edited out page artifacts.

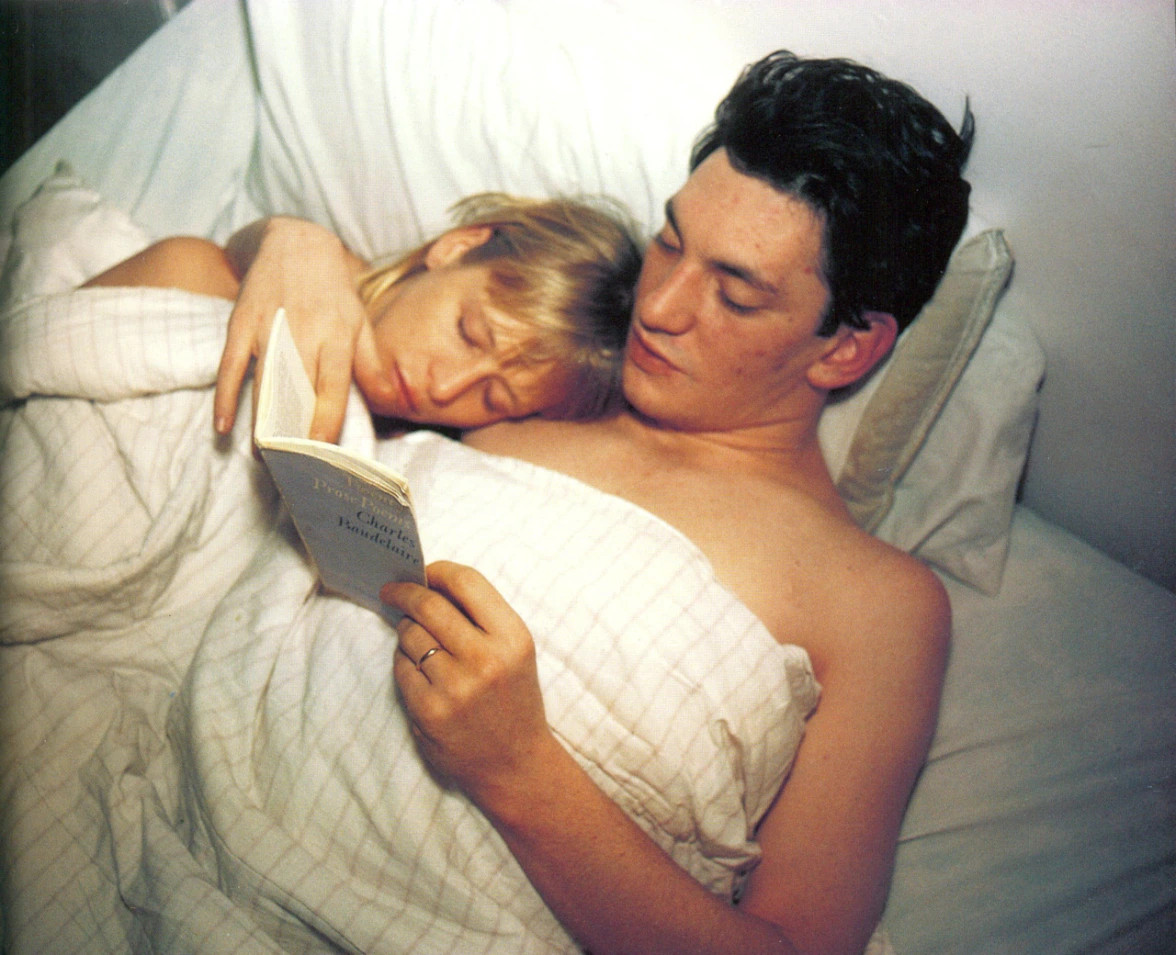

20.1.3: – Photographer: Nan Goldin. Models: Teri Toye and Patrick Fox. Image Source: Wordpress blog.

20.2.1: – Model: Teri Toye. Designer: Stephen Sprouse. Image Source: The Stephen Sprouse Book (2009) by Roger Padilha and Mauricio Padilha, pg. 96.

20.2.2: – Photographer: Robert Kirk. Model: Teri Toye. Designer: Stephen Sprouse. Image Source: New York Time online. Misc: The entire show has been digitized by KCD Worldwide, who refused me access.

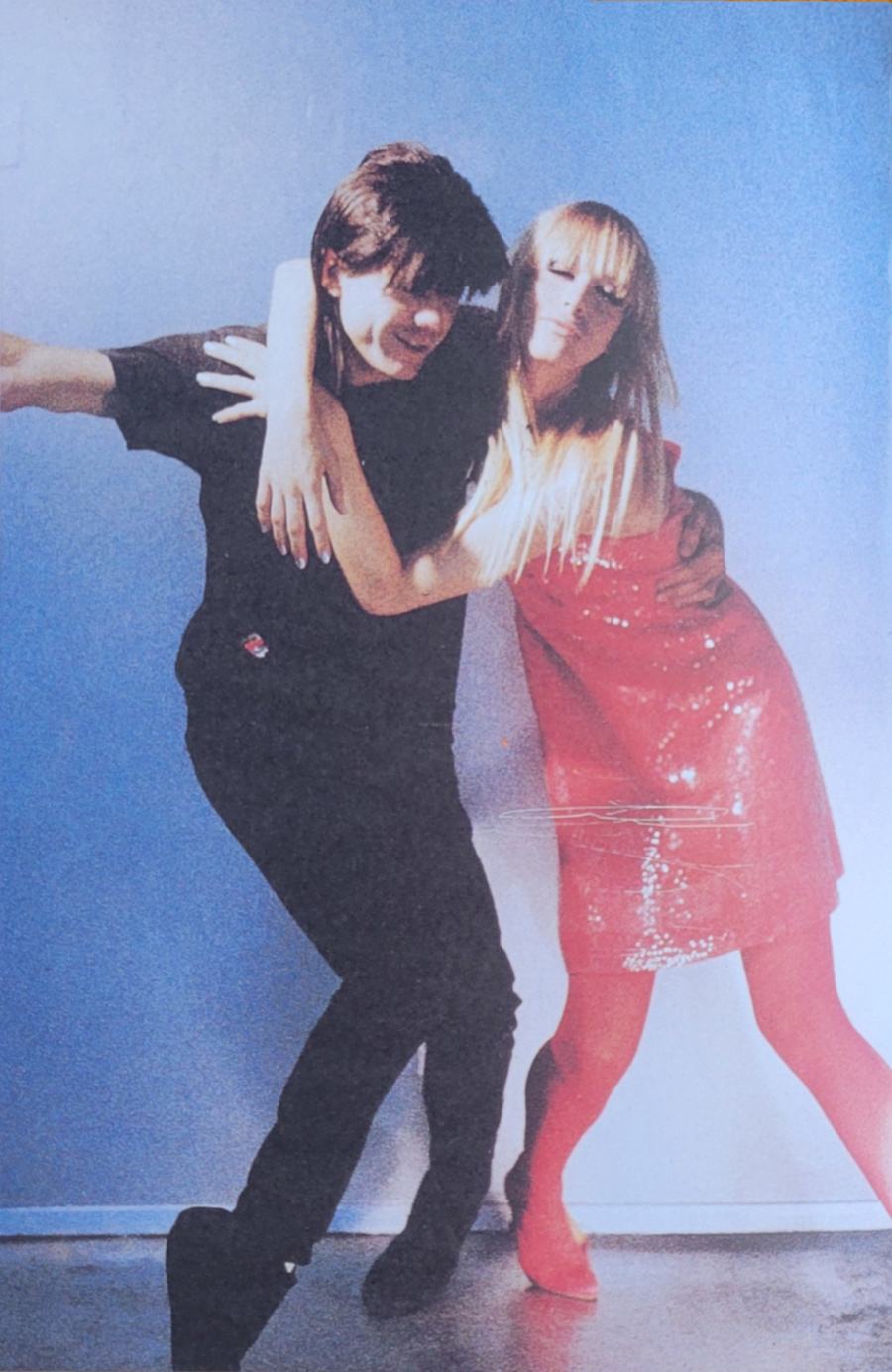

20.2.3: – Photographer: Paul Palmero. Model: Stephen Sprouse, Teri Toye. Designer: Stephen Sprouse. Image Source: The Stephen Sprouse Book (2009) by Roger Padilha and Mauricio Padilha, pg. 82.

20.3.1-4: – Photographer: C. Gerli. Model: Teri Toye. Designer: Thierry Mugler. Image Source: Runway slides at Fashion Institute of Technology, US NNFIT SC.497.966, #150; .967, unlabeled (see also #17); .566, #19, 11.

21.1.1: – Photographer: Tina Paul. Models: Debbie Harry and Willie Ninja. Designer: Stephen Sprouse. Image Source: Pat in the City by Patricia Field (eBook).

21.1.2: – Models: Willie Ninja and Adrian Magnifique. Designer: Thierry Mugler. Video Source: Private collection.

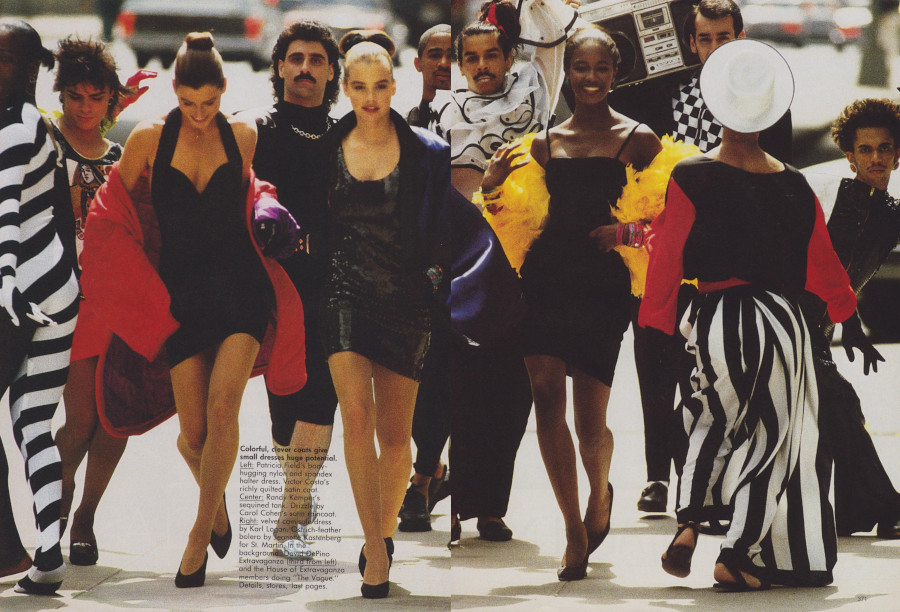

21.2.1: – Photographer: Neil Kirk. Hairstylist: Madeleine Cofano. Maquillage: Margaret Avery. Models: Noami Campbell, Angie Xtravaganza, David DePino Xtravaganza, and others. Image Source: “Fashion: Economy Class” in Vogue, Dec 1988, pg. 370-1.

22.1: – Videographer: Nelson Sullivan. Model: Connie Fleming. Designer: BodyMap. Image Source: 5ninthavenue YouTube channel. Misc: Nelson Sullivan Video Collection content used by permission of Good Dog Blackout LLC.

22.2: – Model: Connie Fleming. Designer: Thierry Mugler. Video Source: Private collection.

23.1-3: – Models: Amanda Lear, Roberta Close, Bibiana Fernández. Designer: Thierry Mugler. Video Source: Private collection.

24.1: – Model: Eva Robin’s. Designer: Chiara Boni. Source: Chiara Boni archives. Misc: My endless thanks to Lorenzo, Ilaria, and Chiara for access and conversation.

24.2: – Model: Carmen Xtravaganza. Image Source: carmenxtravaganza.biz.

B. Ballroom Name Glossary:

This essay uses concurrent house naming for all involved except House of Field, whose members of concern were better known outside ballroom. Out of respect, this short list means to credit civilian names and shifts in house membership for individuals who wished this information to be known.

Marcel Christian, later Marcel Christian LaBeija, off ballroom Herman Williams

Adrian Magnifique, later Adrian Xtravaganza, off ballroom Adrian Alicea

Kevin Ultra Omni, off ballroom Kevin Burrus

Willi Ninja, later Willi Ninja Field, off ballroom William Leake

Tracey Africa, off ballroom Tracey Norman

Carmen Xtravaganza, off ballroom Carmen Inmaculada Ruiz

C. Acknowledgements

I have now certainly reached the level as a researcher that seeking to credit everyone who aided me would be a completely futile endeavor. Thank you especially to Frankie Chillino and Myra Lewis for their extended conversation – if I wound up using little of it in the text, it was important to me personally. Thank you to John Simone, Chantal Regnault, and Robert Coddington for use of their images and archival work. Thank you to Daniel for the extensive conversations about the Mugler archive. And with that I am afraid I must leave the other names alone.

D. Reader’s Bibliography

Unfortunately many relevant texts here are out of print. The Opulent Era by Elizabeth Ann Coleman is the greatest book on Worth, placing him in context. Elizabeth can in general read a garment as persuasively as great literary critics read books, a feat I found no other fashion historian of the period accomplished. I would highly recommend The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm by Ellen Moer; academic criticism these days has lost a lot of beauty and readability in its sentence and argument, of which this book, though dated, is a constant reminder. Worth it even if you have to skip over the untranslated French. There are no good books on the Chevalière d’Eon, especially none in print. Ballroom history is primarily oral and pictoral; I would suggest careful reading of the interviews in Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989-92. On Mugler there is again no serious biographical work, though many large fashion books tangential to my purpose. The best writeup on Teri Toye is by Michael Gross in Model: The Ugly Business of Beautiful Women, pgs. 423-6; the book is in general a tremendous mass of novel information. The Stephen Sprouse Book by Roger Padilha and Mauricio Padilha was beautiful and informative, with much less masturbatory self-congratulation than in most fashion books. The two existing booklength treatments of queerness and fashion, Work! by Elspeth H. Brown and A Queer History of Fashion ed. Valerie Steele, do not highlight trans people much, and are quite academic, but still useful.

1“…des boucles d’oreilles magnifiques, formées de très grosses poires en diamant, qui venaient de la Reine Marie-Antoinette.” Souvenirs intimes de la Cour de Tuileries by Madame Carrette (1889), pg. 178-9

2From Eugenie: the Empress and her Empire (2004) by Desmond Seward, pg. 175; citing Lettres familières de L’Impératrice Eugénie (1935) v. 1, pg. 83.

3All examples littered throughout La Mode Illustrée. See in particular the remarkable article “Modes” in the 1864 collected volume from Firmin-Didot, pg. 53: “Long, puffed skirts trimmed at the edge, tight sleeves, voluminous hairstyles… make us more and more similar to engravings which represent the costumes of Marie-Antoinette. It is becoming obvious the new will be made with old things… In short, fashion will be as Marie-Antoinette as possible.” Noting this is not to deny wider eclecticism in Second Empire fashions.

4See My Years in Paris by Princess Pauline Metternich (1922), pgs. 14-18.

5Letter from Queen Elizabeth to Princess Feodora of Leiningen, Royal Archives Add. A19/37, 6 January 1853. Extended quotation in Queen Victoria: A Personal History by Christopher Hibbert (2001), pg. 231.

6To avoid burdening English readers with particularities of the arrondissements of Paris, I have used “the Bourse” to capture a nebulous geography centered on the 2nd arrondissement, but extending into the 9th (Palais Garnier), the 1st (Les Halles), the 8th (Le Carrousel), and several smaller adjustments.

7Considerable debt for the conclusion is owed to the exceptional paper “Napoleon III's transformation of Paris: the origins and development of the idea” by David H. Pinkney for The Journal of Modern History (1955), vol. 27, nr. 2. The essay is largely repeated as chpt. 2 of his Napoleon III and the Rebuilding of Paris (1958).

8“encourager les institutions destinées au développement de crédit agricole ou commerical,” “satisfaire largement les intérêts légitimes,” and “une vaste conspiration démagogique” from Moniteur universel, Nov. 5, 1851.

9First quotation in Reminiscences by Grace Curzon, as the Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston, G.B.E. (1955), pg. 78. Latter quotations in the fantastic I Am the Most Interesting Book of All: The Diary of Marie Bishkirtseff (1887, trans. Katherine Kernberger 2013), pgs. 89, 158.

10The allusion here is to Veblen’s conspicuous consumption. Too many fashion historians write into the myth that obscene cost of a Worth garment (see fn. 20) was in any sense authenticated by make. Only does Elizabeth Coleman, in The Opulent Era (1989) express courageous disagreement: “an assembly-line approach to dressmaking… a mechanic turning out die-cut apparel.” Worth dresses were bought in order to have bought Worth dresses, and no other reason; haute couture was distinguished not by quality of make, but social relation to customer.

11See My Years in Paris by Princess Pauline Metternich (1922), pg. 60.

12This story has been told and retold in a number of places. See for instance Worth: the Father of Haute Couture (1980) by Diana de Marly, pg. 40; also A Century of Fashion (1928) by Jean-Philippe Worth, pg. 43; Eugenie: The Empress and her Empire by Desmond Seward (2004), pg. 103; for related “toilettes politique” see pg. 172 in the Souvenirs (1889) of Madame Carette.

13See A Century of Fashion (1928) by Jean-Philippe Worth, pg. 7, which also references the Rainbow Portrait of Queen Elizabeth.

14“There is a fine bust of Napoleon the First, and one of Worth the First,” in “Worth, the Paris Dress-Maker” for Harper’s Bazar, February 14, 1874, pg. 116.

15Literally “the Napoleon of costumers” in “Worth, the Paris Dress-Maker” for Harper’s Bazar, February 14, 1874, pg. 116; elsewhere “the king of dress,” etc. The assignation was not original, dating so far back as Louis Hippolyte Leroy; see Kings of Fashion (1958) by Anny Latour (trans. Mervyn Saville).

16See “The Contributors’ Club” in The Atlantic, February 1884, pg. 282. Written, obviously, after the fall of Napoleon III.

17“l'illustre Worms, le tailleur de génie, devant lequel les reines du Second Empire se tenaient à genoux,” from La Curée (1871) by Émile Zola; usefully translated as epigraph to The House of Worth 1858-1954: the Birth of Haute Couture (2018) by Chantal Trubert-Tollu et al.

18From “The Man-Dressmaker of Paris” in Harper’s Bazar, December 21, 1967, pg. 123.

19See pg. 66 in Dress (1878) by Margaret Oliphant, quoted on pg. in Worth: the Father of Haute Couture (1980) by Diana de Marly, pg. 219. It should be clarified here that, as delicious the quote is, Marge was a rather stodgy writer addressing the middle classes.

20Historical exchange rates must be taken with a mountain of salt. Worth claimed in 1871 his cheapest day dress was 1,600 francs (just under 10,000$ today); in 1895 Worth asserted customers spent “a minimum of £400” (just over 50,000$ today). His most expensive gown ever produced was 120,000 francs (over half a million today). Every Worth historian includes a discourse on cost; Worth (1980) by Diana de Marly, pg. 100 is concise.

21See again Worth (1980) by Diana de Marly, pg. 101: “a clear profit of over £40,000 a year.”

22From start Worth was primarily an international phenomenon. French women purchased his dresses, but he was relatively unreported in French periodicals until the 1880s. See the FIT thesis Charles Frederick Worth: A Study in the Relationship between the Parisian Fashion Industry and the Lyonnais Silk Industry 1858-1889 (2003) by Sara Elisabeth Hume, pg. 11. Contemporary French histories of fashion still tend to downplay his contribution; others exaggerate it.

23All quotations lifted from the excellent Husband Hunters: American Heiresses Who Married into the British Aristocracy (2018) by Anne de Courcy, pgs. 4, 230.

24Some Memories of Paris (1895) by F. Adolphus, pg. 194.

25A Century of Fashion (1928) by Jean-Philippe Worth, pg. 102.

26This assertion may be taken as poetry, since there is no credible research on pageantry before Miss America this author knows of. Beauty contests date to the Judgment of Paris; “queens of beauty” are symbols throughout English poetry, particularly for Romantics; but the earliest historical beauty queen on record was at the Eglinton tournament of 1839, attended by Napoleon III. By 1880, the title was familiar, promoted by local business, and condoned by state.

27Manchester Evening News, 20 March 1895, as cited in The House of Worth: Portrait of an Archive 1890-1914 by Amy de la Haye and Valerie D. Mendes, pg. 125.

28Days I Knew (1925) by Lillie Langtry, pg. 137, as cited in Haye & Mendes, pg. 129.

29“The Man-Dressmaker of Paris” in Harper’s Bazar, December 21, 1967, pg. 123.

30My Years in Paris by Princess Pauline Metternich (1922), pg. 57.

31“…one of them [‘the shop-girls’]… wore a splendid diamond ornament resting on her forehead. This proved to be the wife of Worth…”; “The Man-Dressmaker of Paris” in Harper’s Bazar, December 21, 1967, pg. 123.

32“Les Premières” by Sophie de Maucroix in Cassell & Company compilation of The Woman’s World ed. Oscar Wilde, Vol. 1 (1888), pg. 205.

33From “History of Bonnets in Queen Victoria’s Reign” by Isabel Cooper-Oakley in Woman’s World, Vol. 1, pg. 507.

34“Women Wearers of Men’s Clothes” by Emily Crawford in Woman’s World, Vol. 2 (1889), pgs. 283-6. A remarkable document, extremely anti-Worth, celebrating “Sarah Bernhardt’s mannish garments.”

35“Literary and Other Notes” by Oscar Wilde in Woman’s World, Vol. 1, pg. 40.

36These quotes are from the early Oscar Wilde essay “The Philosophy of Dress” and lecture “House Decoration.” See the immensely useful Oscar Wilde on Dress (2013), edited, with considerable commentary, by John Cooper.

37Napoléon Sarony (1821-1896), whose first name I have omitted simply to avoid introducing yet another Napoleon.

38“La forme presque féminine de ses traits” and “une jeune fille déguisée.” Using the Robert M. Adams translation (1969), pg. 23, 21.

39As Ellen Moers notes repeatedly in Chpt. III of her field-defining The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm (1960), Pelham (1928) received significant revisions in later editions. Ellen is however incorrect that “Bulwer was not afraid of the term” effeminate “in the first edition of the novel only” (pg. 81), as this quote appeared only in later editions. See The Works of Edward Bulwer Lytton (1892), vol. VIII, pg. 199.

40“Les hanches de l’Antiope au buste d’un imberbe” from “Les Bijoux” (trans. Richard Howard). Baudelaire is exceptional among examples here in that he locates androgyny in his lovers but never his own person.

41“il en vint à éprouver, de son côté, l'impression que lui-même se féminisait” and “un artificiel changement de sexe,” adapted from the Roger Baldick translation (1956) for Penguin Classics, chpt. 9.

42See The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde (2003) from Merlin Holland (Oscar’s grandson) for an uncensored trial transcript; pgs. 94-100 for mentions of Huysmans’s Against Nature.

43“Le dandysme apparaît surtout aux époques transitoires où la démocratie n’est pas encore toute-puissante, où l’aristocratie n’est que partiellement chancelante et avilie.” From The Painter in Modern Life (trans. P.E. Charvet, 2010).

44“mené par le démon de la contradiction” in The Book of Masks by Remy de Gourmont, trans. Jack Lewis.

45Although there exists a slew of gay slang dictionaries, almost none show etymological research. A happy exception is “Gay Slang Lexicography” (2005) by Gary Simes for Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America, 26.1, pgs. 1-159. It features citation to a “first” gay slang glossary by I.L. Pavia in 1910 which asserts “Quean (with ‘ea,’ not, as might be thought, queen = female monarch) means ‘whore’.” The decadent movement, at least, destroyed this distinction. Useful correctives are found in Gary’s own compendium on pg. 71, citing with priority Oscar Wilde.

46See Mallarmé on Fashion: A Translation of the Fashion Magazine La Dernière mode, with Commentary (1874, trans. P.N. Furbank & A.M. Cain, 2004), pg. 5.

47“Le Dandysme, au contraire, se joue de la règle” “contre l'ordre établi, quelquefois contre la nature” in Du Dandysme et de George Brummell by Barbey d’Aurevilly, published under The Anatomy of Dandyism (1928, trans. Wyndham Lewis), pg. 10.

48For Selwyn mention see Anatomy of Dandyism, pg. 28. The quote itself is from Historical Memoirs of My Own Time (1815) by Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall, pg. 298 in 1837 omnibus from Carey, Lea, and Blanchard.

49Though a committed bourgeois, Charles Worth had more dandyism than typically acknowledged. Dandy novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Night and Fog “made a profound impression on him, had awakened his genius, aroused his courage, kindled his hopes.” He named a son for the novel. See pgs. 10, 30 in Worth: Father of Haute Couture (1990) by Diana de Marly; with original citation to Personal and Literary Letters of Robert, First Earl of Lytton, ed. Lady Betty Balfour (1906), vol. 1, pg. 307. In conquering a female trade as a man, he violated a gender barrier. He was in this sense “queer” as the dandy, though this is frankly overstated. See Abigail Joseph, “‘A Wizard of Silks and Tulle’: Charles Worth and the Queer Origins of Couture.” Victorian Studies 56.2 (2014): 251-279.

50My Years in Paris by Princess Pauline Metternich (1922), pg. 66; also Worth by de Marly, pg. 56, Birth of Haute Couture by Trubert-Tollu et al., pg. 34, etc. Italics mine.

51Napoleon’s Marshalls (1909) by R.P. Dunn-Pattison (1909), pg. 51. Said of André Masséna.

52See vital essay “The myth of the female dandy” by Miranda Gill in French Studies 61.2 (2007): 167-181, without which this essay might not have proceeded.

53From the excellent Napoleon and the Woman Question (2007) by June K. Burton, pg. 5.

54The most curious and robust offender, comparatively, was Proust. Broadly overlooked in dandy studies, he credits Andrée in the second volume of Lost Time with “le flegme souriant d’un dandy femelle”; no sure compliment, Albertine’s potential dalliance with Andrée, as well as the possibility of lesbianism, or independence of the beloved from the Narrator generally, are the primary antagonists of the text.

55“La femme est le contraire du dandy… La femme est naturelle” and “son dandysme de femme froide,” translated by Richard Sieburth in Late Fragments (2022), pgs. 112-113, 98.

56See Walter Benjamin’s “Central Park” (1939), trans. Lloyd Spencer and Mark Harrington in New German Critique 34 (1985), pg. 35. Charlotte D’Eon’s own personal heroes – Amazons of Greek myth, Hannah Snell, Joan d’Arc, and Mary of Nazareth – will all fit this female dandy template, as does she.

57Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman (1995) by Gary Kates, pg. 187, citing “Box 10, 335” of the d’Eon collection at Brotherton Collection at the University of Leeds, which I sadly could not visit. They have not been digitized.

58See George Selwyn: His Letters and His Life (1899) ed. E.S. Roscoe and Helen Clergue, pgs. 117-8.

59Kates, Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman, pg. 71, 100; The Maiden of Tonnerre: The Vicissitudes of the Chevalier and Chevalière d’Eon (1785), trans. Roland A. Champagne, Nina Ekstein, and Gary Kates (2001), pgs. 135-6.

60“Je suis assez mortifié d'être encore tel que la nature m’a fait” in letter of Chevalier d’Eon to Broglie, 7 May 1771, from Mémoires sur la Chevaliere d’Eon (1866) by Frédéric Gaillardet, pg. 193.

61Kates, Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman, pg. 71.

62“Je vais me charger de son trousseau” in Le Chevalier d’Éon (1998) by Michel de Decker, pg. 210.

63Kates, Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman, pg. 30.

64This was the important Rose Bertin, whom after some consideration I elected not to discuss. On Rose, see Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, Minister of fashion: Marie-Jeanne ‘Rose’ Bertin, 1747-1813. Diss. University of Aberdeen (2002); or Emile Langlade, Rose Bertin, The Creator of Fashion at the Court of Marie Antoinette, trans. Angelo S. Rappoport (1913).

65Maiden of Tonnerre, pg. 59, 134.